SARAH WALDRON covers the sentiment of Americana while discussing the rise of this all familiar style and its effects on the fashion industry for the latest issue of D’SCENE Magazine.

Think ‘Americana’ and you’ll probably think about the last two and a half centuries. Star-spangled banners. GIs. Rock and roll. A glass bottle of Coke on a hot day, one perfect drop of water beading its way down, navigating its Belle Epoque curves. Aggressive partisan politics and overseas wars. Still, now, people think of these things whenever the home of the brave and the land of the free heaves into the periphery.

But that’s not really what Americana is. It is the red, white and blue – of course it is – but it’s also the dark and the light; a land in which nature took precedence over God, and communities were formed on a much smaller scale.While Native Americans were quickly beaten back by disease, colonial might and cultural ignorance on the East coast, by the mid-nineteenth century they were still a force to be reckoned with. But not for long.

In the fashion world, Americana has come to represent a sartorial mix of white settlers and Native American design, encapsulating the moment when one frontier surged forth to meet the other. In 1862, the American Homestead Act sold pockets of land in faraway states for a pittance and 600,000 families went to meet the West. Others inevitably followed, which lead to conflict, mutual distrust, violence and the eventual marginalisation and abuse of an entire race of people.

It’s so odd that fashion, an ostensibly shallow medium, would offer a more accurate and evocative visual reading of the world ‘Americana’ than other, more prominent cultural method of communications (think literature and art), but there you are. Fashion can surprise you sometimes. And while it’s far from perfect in its representation of the duality of old and new cultures at war, it’s still much better than the alternative.

Prairie chic – as seen on the catwalk at Simone Rocha, Alexander McQueen and Coach – translates to a hardy utilitarian demureness. Hardworking fabrics meet feminine ruffles, Victoriana high-necked collars and buttoned up exteriors. In fresh virginal white marked spots of handworked lace or wildflower print, these dresses are a straightforward interpretation of actual period designs worn by homesteaders making their way steadily across the plains. For Spring/Summer at Erdem, the trend went a little deeper, delving into the psychological affliction known as ‘prairie madness’, which manifested itself in settling men and women who found the approaching landscape too bleak, too isolating, too harsh and indifferent. Reminding us that the women of the prairie could be suppressed and not free-spirited, the delicately wrought dresses prioritised delicacy over the prairie’s typically hardy appearance. Floral pieces with a surplus of layers had an air of elegant, deconstructed decay – the foundation wardrobe of a Ms. Havisham of the plains.

Native American garments are often nauseatingly appropriated and repurposed as festival gear (war bonnets at Coachella, anyone?) but there has historically been some crossover between settlers and tribes. Beads and blankets were big sellers. In the southwestern states of America, the Navajo nation were known for their instantly recognisable woven blankets and rugs, as well as the silver and turquoise jewellery that we see so many different permutations of on the high street today. Used, worn and traded with white settlers, these motifs bled into the Americana image, mixing the fashion DNA of settlers with Native Americans. Unfortunately, this remains as close to an entente as the two groups would ever get.

In fact, ‘navajo’ has become an overarching and incredibly inaccurate term for all Native American or even vaguely abstract Native American-inspired designs. In 2011, the Navajo Nation filed a lawsuit against American retailer Forever 21 asking for a percentage of profits from the brand’s Navajo line. In May of this year, they lost the lawsuit, the judge ruling that ‘navajo’ was, in fact, a blanket term and that the nation themselves were not famous enough to merit a trademark – all this despite the obvious fact that their designs were indeed famous enough to become universally known. It’s a very modern kind of legal exploitation.

When it comes to Americana, notions of femininity are also picked apart. People had no choice to be anything but physically hardy, so ruffled and frilled clothing was built to withstand harsh conditions. Dresses were made to be worn with clodhopper boots. Ankle-flashing hems were raised scandalously, inches above the socially accepted, floor-sweeping norm, to facilitate a greater range of movement movement and restrict the tracking of mud, dust and rain from place to place. In this way, mental and physical toughness became part of the American style vocabulary, and this wouldn’t change until the post-War era. Swooning Southern belles, despite their cartoonish femininity, are not very Americana. Here, being womanly also involved strength and fortitude – something that is very much a part of contemporary American can-do consciousness.

The weight of history can be almost unbearable, and when you throw more than a dollop of colonialism into the mix… Well, Altas would still struggle. And yet, Americana fashion – true, original Americana; a protracted clash of settler and Native American – can still be encapsulated by the simple visual of one woman in one simple outfit. A white dress. A patterned shawl. A pair of boots.

Words by Sarah Waldron (Twitter/Instagram), illustration by Shira Barzilay @koketit

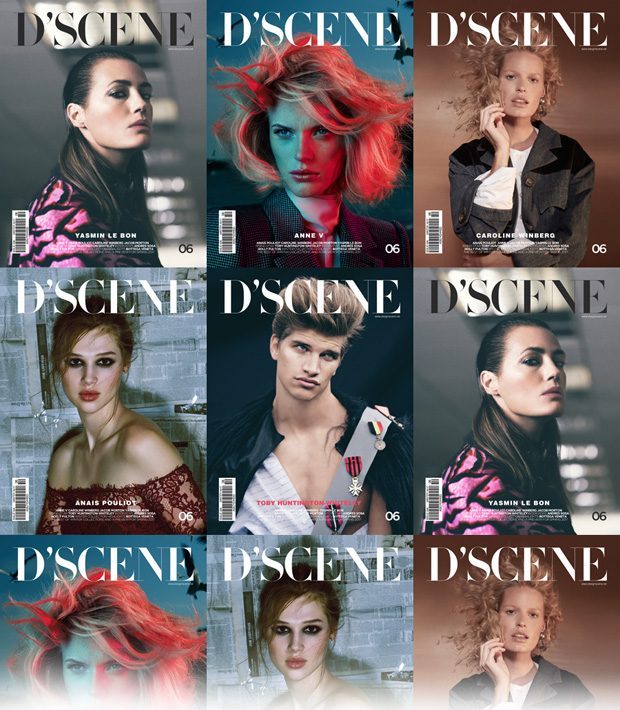

Originally published in D’SCENE Magazine 06 – OUT NOW