And with those words, the gauntlet for 2017’s zeitgeist is thrown down. The most influential designer of the 1990s is back. Or is he? D’SCENE Contributing Writer HARRIET MAY DE VERE wonders if this is a true comeback while investigating the phenomenon of Helmut Lang then and now.

AVAILABLE NOW IN PRINT & $4.90 DIGITAL

In 1977 Helmut Lang launched his made-to-measure studio in Vienna, Austria. Lang’s constructions first appeared to the mainstream in the 1986 exhibition Vienne 1880-1939: L’Apocalypse Joyeuse (The Joyful Apocalypse) at Paris’s Pompidou Centre, starring alongside works by Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oscar Kokoschka; some of the most dramatic examples of European genius. The fate of Helmut Lang has long since played out, but has hindsight earned him a place among these names?

Read more after the jump:

The exhibition programme previewed a barren aesthetic that would become associated with the eponymous company Lang founded later that same year. Helmut Lang the brand is vividly Austrian. That stark temperament, with a slight nudge towards austerity, has since become almost formulaic in central European design. Hygge, koselig, lagom; before all of these trends, there was Helmut Lang. Black Futura on ivory. WEAR. HELMUT. LANG. Never has sterility been so stimulating.

To millennials, 1980s and 1990s fashion is brash and obnoxious; adjectives that trigger veneration on Instagram. Social media is saturated with ‘throwback’ dedications to logomania, oversized hiphop shapes, Thierry Mugler power suits, Christian Lacroix gold enamel, but this ode to excess is just one side of the story. Nineties minimalism was eighties’ gluttony’s rebuttal. Off the back of the 1980s success of Yohji Yamamoto, and Rei Kawakubo’s Commes des Garçons, Helmut Lang’s seemingly-spartan designs became wildly popular. “Clothes are not only about putting them on,” Lang would say, “They are also about taking them off.” They screamed nudity, not in the brazen, flesh-baring way of today, but with a brush of the nipple, or a flash of lingerie peeking through a skirt turned momentarily sheer as it catches the light. Lauded as ‘minimalism’ far and wide, Lang always refuted this stereotype. His raw-edged, neutral-palette collections of filmy clothing, he argued, were the “modern elaborate”. Either way, Vogue elected Lang responsible for ‘The coming of the age of cool’.

Helmut Lang Resort 2018 advertising campaign

Helmut Lang Resort 2018 advertising campaign

Few measured up to Lang’s raw aesthetic standards, but those who did became integral to his quickly escalating technology-lead machine. Melanie Ward was the stylist in the days before everyone was a stylist. Ward met Helmut Lang in Paris in 1992. Their connection was instant, as Ward put it, “I’ve never met anyone who had such similar taste to me, they used to call me the female Helmut”. They began collaborating and eventually, to the horror of many of Lang’s rivals, Ward was working exclusively for the brand. Wards’ self-diagnosed “documentary style” aesthetic became synonymous with Helmut Lang.

Ward and Lang advertised in National Geographic magazine, instead of Vogue. They printed artists such as Louise Bourgeois and Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs for their campaigns, crediting the artist but also including the Helmut Lang logo, as if they could culturally appropriate high art’s prestige. They showed in Paris at the industrial white space of the Espace Commines, until in 1997 the pair of them decided they’d had enough of imitators and moved their show weeks ahead of schedule to New York. Traditionally New York had been the grand finale in the fashion week cycle, but such was the extent of Lang’s influence that the industry followed him, creating the New York-lead schedule we have today. At the turn of the millennium the world was at Helmut Lang’s feet.

The delivery of ideas in public spaces was at the core of Helmut Lang psychology. He was an early adopter of the internet, choosing to show his Fall 1998 collection on CD-ROMs. He began the process of democratising and declassifying the viewing of fashion towards an everyone’s-welcome art gallery mentality. During this period Lang was introduced to artist Jenny Holzer by Interview’s then editor-in-chief, acclaimed art critic Ingrid Sischy. Holzer later described her and Lang’s synchronised tastes as “a little mean, and less-is-more”. They began learning each other and eventually collaborating. Hundreds of cabs swarmed New York with ‘HELMUT LANG’ – no image, and seemingly no product – lit up on their roofs. Just black, white, and Futura Condensed font triggering desire.

Lang and Holzer’s combined talent culminated in the 2000 launch of the brand’s first fragrance. To the industry it was as if he was selling thin air. Ever the tecnophile, Lang chose to launch the fragrance – as Vogue remarked – ‘on, of all places, the Internet’. Beauty editors were aghast; why sell scent that can’t be smelled? It became a cultish success, with critics calling it ‘The Zeitgeist Bottled’ and fans scouring online forums and eBay for half-empty bottles when it was discontinued in 2005. Alexander Wang, Supreme, Vetements, in Lang’s wake brands have constantly demonstrated what he knew. It is concept, not product, that sells high fashion. Why else in the nineties would you pay $200 for jeans? Forget Midas, in 2000 it was Lang’s touch that turned everything to gold.

So why isn’t this man lauded with the Gianni Versaces, Yves Saint Laurents, Coco Chanels and Christian Diors of this world? Why, as someone who is interested in fashion, could you have only heard of him in the last year or so? Jenny Holzer, as you may know, recently collaborated with fashion’s current darling Virgil Abloh for his brand Off White’s SS18 show. Where is Helmut Lang?

In 1999, high fashion conglomerate Prada Group bought a 51% majority stake in Helmut Lang. Then in 2000 the designer was nominated in three categories, winning the Menswear Award, at the Council of Fashion Designers of America Awards, aka ‘the Oscars of fashion’. He did not show up. He continued to work quietly as creative director under Prada until three years later when he sold the remaining 49% of his shares, handing total control and his name to Prada Group.

Fast forward over a decade. The world has had another boom, another slump, and a lot of bashing. The kitschy cool excess of the 2000s has given way to loss. The world feels unstable and consumers want security anywhere they can grab it. Prada has long-since sold Helmut Lang to Link Theory, a Japanese retailer. Brands who offer sustainable luxury, who sell garments that hold their worth, that are timeless not showy, are succeeding among those who remember the Lang years. Celine, Raf Simons, Rick Owens, countless current designers owe a debt of gratitude to Helmut Lang. As Alix Browne at W Magazine so eloquently surmised, ‘Helmut Lang’s influence is everywhere, it seems, except in the brand that still bears his name’.

A few months ago Kanye West was spotted in a pair of Helmut Lang paint-splattered jeans from the brand’s 2000 heyday. West has cited Lang as an influence many times, admittedly citing him as one of his only four references when critics matched his Yeezy Season 1 looks explicitly with archive Helmut Lang. German fashion designer Bernard Wilhelm even went so far as to say that he’d ‘heard from people working at different fashion houses that there is always a Helmut Lang piece hanging and it’s right there to be copied.’ When everyone’s forging your signature, it’s time to design a new one.

Helmut Lang Resort 2018 advertising campaign

Helmut Lang Resort 2018 advertising campaign

When other brands start translating your legacy to a new generation, it’s time to step in. At the beginning of 2017 something was in the air at Helmut Lang. Whispers of a relaunch were trickling along the industry grapevine. March arrives, and with it comes Dazed’s Isabella Burley being anointed Helmut Lang’s first Editor-in-Residence. Also officially linked to the brand, but under hazier guises, were Hood By Air founder Shayne Oliver and tongue-in-cheek bootleg fashion creator Ava Nirui. Words start to appear on the brand’s Twitter; ‘WARNING LACK OF CHARISMA COULD BE FATAL’, ‘IMPRESS YOUR PARENTS’, ‘WEAR HELMUT LANG’.

“It’s really important for Helmut Lang to be an authority on Helmut Lang again,” Burley stated this summer as she announced her initial intentions for the brand. She planned to ‘re-edition’ (in the tone of an artist’s estate) originals from the Helmut Lang archive, and fifteen pieces, including the infamous paint-splattered jeans of 1998, went on sale in September. In Helmut Lang’s original spirit, Burley has also invited a dozen artists to collaborate on ad campaigns and limited edition items. The much hyped SS18 show at New York Fashion Week was billed as ‘Shayne Olivier for Helmut Lang’; a canny way of removing some of the pressure of living up to the brand’s legacy. The reviews were mixed. For some Oliver’s overt sexuality, such a hit at Hood by Air, was inappropriate at a brand who made their name with subtlety. It remains to be seen whether this dream team, the cream of today’s industry, can get it right.

But what became of the man? Often the fashion industry consumes the PR folklore around a founder to the extent that the real story becomes blurred or forgotten. The fashion houses play up to it, using these human stories to give brands humanistic personification. Chanel’s Gabrielle perfume adverts, Audrey Tautou as Coco Chanel, Pierre Niney as Yves Saint Laurent; these are idealistic portrayals of designers. Others do not fare so well, no story can cover their tracks. Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, these artists, humans, went to such lengths to get their vulnerability recognised, but it is only with hindsight that aid was offered. When looking back, the industry remembers they’re not a concept, an abstraction, or a hypothesis for a marketing campaign, but a person. To some Helmut Lang lost everything, but he never lost sight of this.

After leaving Helmut Lang the brand, the designer applied for an artist’s studio permit from the East Hampton town board and donated thousands of items from his archive to museums the world over. In 2011 he unveiled the art exhibition ‘Make It Hard’; some 6000 items of Helmut Lang clothing, 25 years of work, shredded, mixed with pigment and resin and reformed into twelve sculptures. Helmut Lang had always been an artist trapped in a businessman’s world. He may have left his name behind, but he didn’t leave his identity.

In 1992, Kurt Kocherscheidt, an artist and close friend of Lang’s, died of a heart attack. Lang cast his grieving widow in his runway show, offering her a chance to regain her sense of self in light of heavy loss. Lang’s muses were always characters of unconventional beauty. He never allowed the current crop of It models to walk the runway more than once per show. The notion of using beauty that isn’t typical is a movement the current generation of designers thinks they invented. Every seemingly nonsensical move Lang ever made always made sense after the fact. Just like technology, after it’s been invented it’s like it was always there.

Perhaps Helmut Lang the brand and Helmut Lang the person have both reached a place of contentment. Shayne Oliver said of the SS18 collection, “When [Lang] first became relevant, clothes were clunky and felt a bit overdone for no reason, and he made them human. I think the human needs to be a bit more present again.” Has the Zeitgeist been reclaimed? Only time will tell.

Text by Harriet May de Vere – harrietmaydevere.com

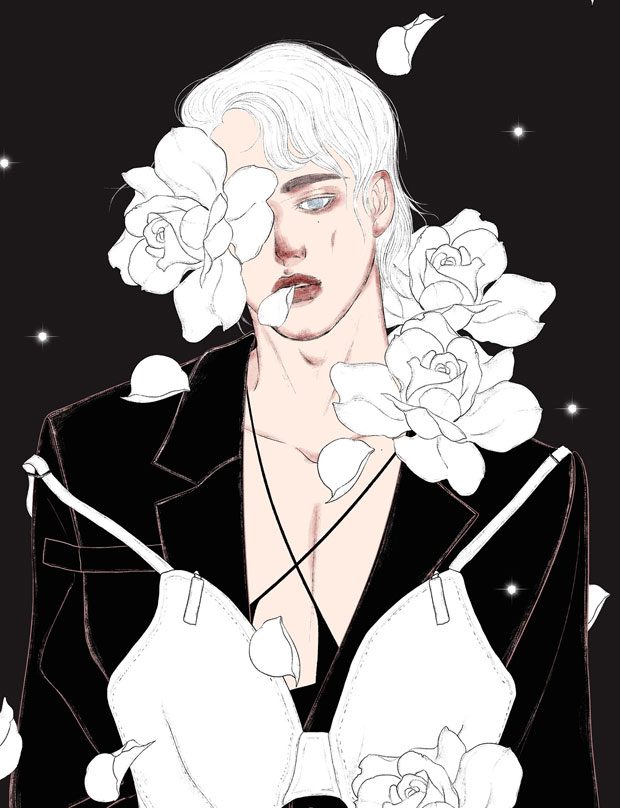

Illustration by Shibo Chen @shibochen

D’SCENE Magazine’s Defiant issue is available now in print & digital.

D’SCENE Magazine’s Defiant issue is available now in print & digital.