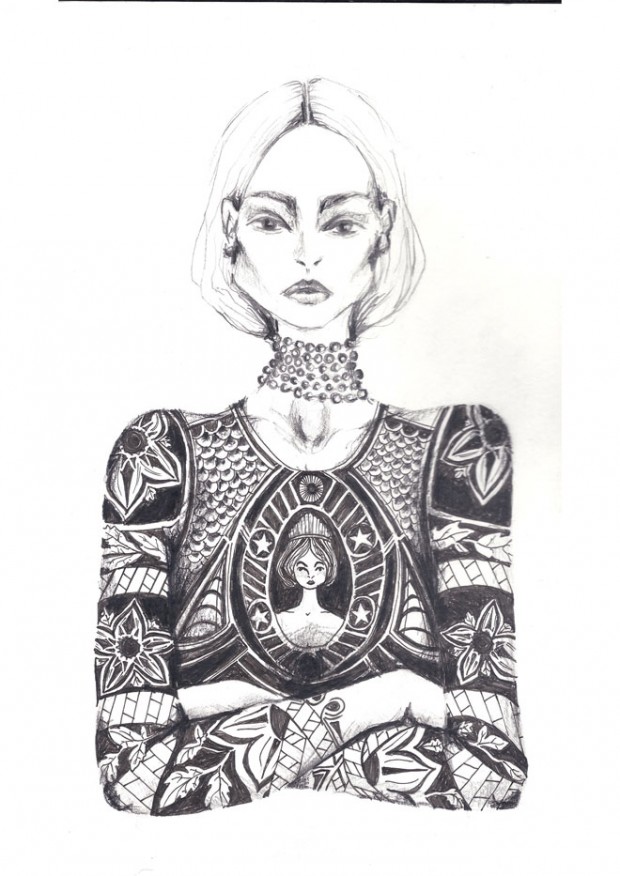

The Inked Woman story from our sophomore issue of DSCENE Magazine by SARAH WALDRON considers the first tattooed women and tackles the public perception of them today. The impressive illustration is courtesy of Illustrator Imogen Bowman..

Best tattoo ideas for men are easy to find, yet when it come’s to women and tattoos the story is much more complex with a far deeper meaning behind the artwork as Sara investigates:

Olive Oatman wasn’t the first tattooed lady, but she may be the most remarkable.

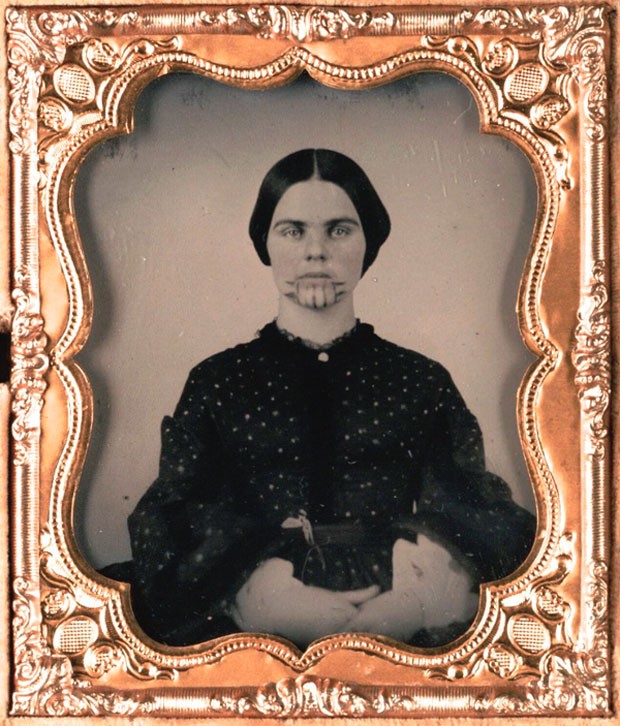

In 1851, Oatman was thirteen. She was travelling with her family from Missouri towards Zion, a Mormon settlement in California, when they were attacked by Yavapai Native Americans. They took Olive and her sister captive and left everyone else for dead. The Yavapais kept the Oatman girls as servants until they were sold to a Mohave tribe a year later. Olive was integrated into the Mohave. When she emerged back into the white world in 1856, she wore her new nationality for everyone to see. Upon her stern but not unbeautiful face was a blue tattoo; four vertical lines and triangles running from mouth to chin. She became a national sensation. Photo above Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Tattoos have been around for thousands of years, existing in almost as many social contexts. Only recently has the tattoo been floated as a fashion statement, despite that fact that only clothes and tattoos are specifically designed to be worn on the body. For those who came to hear Oatman talk (the circumstances around her life and supposed rescue made her a media sensation), the tattoo was the main talking point. Here was a woman who looked like every other. A mere four lines drawn in ink made her a physical anomaly, an exotic outcast.

A tattoo is ownership. For Oatman, it was a permanent reminder that she was always a Mohave, no matter who her parents were. Later on, tattooed women would come to symbolise ownership of a different kind – the ownership of the self. It took a very special kind of woman to have her whole body tattooed as an investment, and these women were not in short supply. Tattooed ladies working in sideshows in the latter quarter of the nineteenth century could expect about a hundred dollars a week. Dancers at the same sideshow would earn about eight dollars. Tattoos meant money, and money meant freedom.

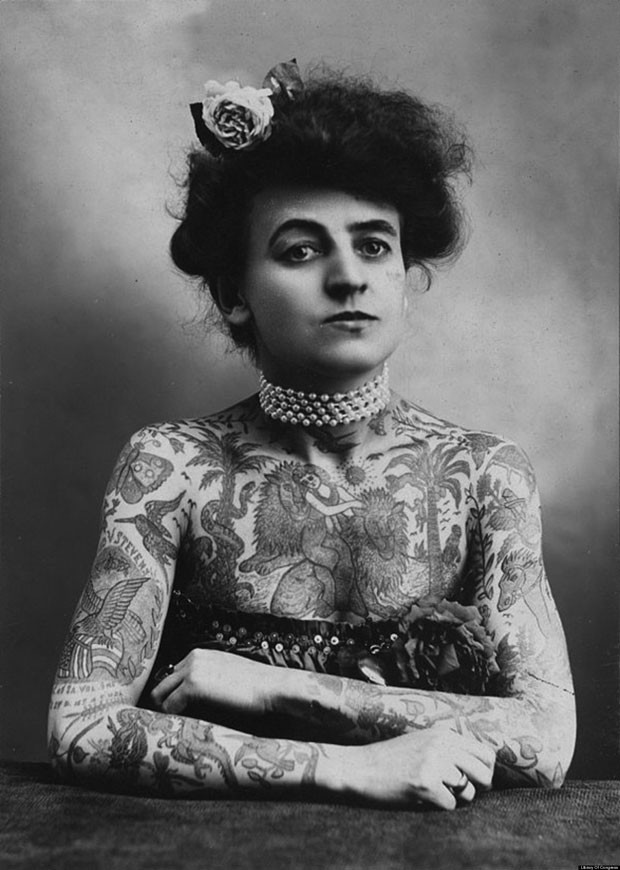

Maud Wagner, the first known female tattoo artist in the United States, only agreed to date her future husband if he gave her a lesson in tattooing. By the time the couple married and had a daughter (who, herself, gave her first tattoo at nine years old) Maud was covered in drawings; a lady and a lion on her chest, snakes writing sinuously up palm trees above her breasts, a swallow atop her clavicle. Wagner was a walking illuminated manuscript. Photo above Library Of Congress

A tattoo is so much more than an identifier. What once spelled a path out of poverty is now a different, but equally powerful, way to a woman assuming autonomy over her body. Because tattoos are often so personal, they transcend notions of class or taste. A tattoo belongs only to the person whose skin bears its marks. A person who passes judgement on the tattoos of others passes it in an invalid way. Aesthetic revulsion is not a justification for condemnation. That logic just won’t hold up in court.

But is a tattoo a valid fashion statement? All signs point to no. While attitudes have shifted and tattoos have become more a symbol of mild rebellion than social suicide, the act of being tattooed has yet to convincingly find its way onto a trend report. Tattoos can be stylish, yes. But fashionable? Never.

That being said, tattooed women veer into the fashion world, as fashion women veer into the tattoo world. Think of Cara Delevingne’s finger tattoos (at current count there are four; a lion’s head, a dove, a heart and a wasp), Jourdan Dunn’s winged Egyptian goddess, Isabeli Fontana’s evil Care Bear – all of them less ‘cuddly’, more ‘claws’.

But when it comes down to it, fashion is fleeting. Trends are temporary; they exist only in a series of moments, preserved only when there is a pen and paper or a camera around to capture it. Even then, the pen can capture only one impression; the camera, only one angle.

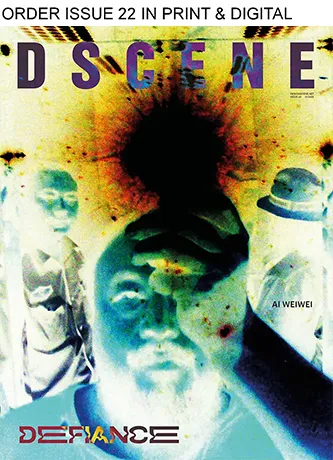

RELATED: Read the interview with our tattooed D’SCENE cover boy STEPHEN JAMES

People wear clothes to express who they are, but tattoos express the essence of a person. While an outfit says a lot about a person’s occupation, values, likes, dislikes and social status, the tattoo tells a story often burdened with feeling (I am now remembering, shamefully, asking a man I had just met what his tattoo meant, only to have him dissolve into tears over the death of a loved one).

Getting inked is much more personal – and much more permanent. A tattoo moves with the skin. It can only be removed with several laser treatments, and even then can never be entirely removed. The shadow of a tattoo will always haunt its owner.

A tattoo is a personal statement, rarely a fashion statement. What a shame that the underlying reason many people give for not liking the tattoos on other people is because ‘it looks cheap’ – the curtain pullback that reveals a collective disgust. Good girls don’t get tattoos. Tattoos aren’t nice. Tattooed ladies don’t fit the narrow womanly mould.

It’s an amazing world we live in, when we are raised not to judge people on the skin they’re born with, but make blithe assumptions (no class, oh so tacky) when we consider a physical change that a woman has planned for herself. Weight loss – you look great! Fake tan – have you been on holiday? Highlights – that really suits you! A chest piece tattoo – what were you thinking?

Ink scratches only the surface. It will not change a person. The mark that can do that, can’t be seen on the skin.

Written by Sarah Walrdon for D’SCENE Magazine #02