Editor ZARKO DAVINIC sits down for an interview with WALEAD BESHTY to talk about his famed FedEx Boxes series, globalization and his work in academia.

DSCENE 014 IN PRINT $12 OR DIGITAL $4.90

Read more after the jump:

What’s it like to talk to people about your art? Is it alienating? Helpful? I tend to enjoy it, but like anything, it depends on the context. Regardless of context, discussing anything can be useful as a way to get your thoughts in order. Even poor contexts – provided you have the time and energy to engage – can often be productive.

When did you know you wanted to become an artist? Was there an exact moment when you decided creating art will be your life? I never really wanted to “become an artist,” rather I slowly figured out that the term best described the sorts of activities I wanted to be involved in. One positive aspect of the profession is that it encourages you to continually re-evaluate the professional conditions under which you work, and moreover, it is flexible enough to adapt to changing priorities and interests, which means the nature of the job evolves over time.

When talking to students who want to pursue art yet are worried about making it financially-how do you encourage them to persist? The way one practices being an artist varies greatly, as does how one makes a living out of it. Unlike other professions, there is not a set career path in art that one can rely on for guidance, that is one of the things that makes it both attractive and daunting. Being an artist forces you to figure out a way to deal with the instability of shifting receptions to your work, and the vicissitudes of the free market, both on a professional and a psychological level. In this regard, a teacher can give guidance, but mostly I think what they can offer is a realistic description, even if only anecdotal, of how the system functions. In the end, one defines for themselves how one wants to go about the profession. This is also a very different question if it is posed within the context of an undergraduate versus a graduate education. I’m a strong believer in a liberal arts education at the undergraduate level, so in that instance, the goal of teaching art is one of visual and aesthetic literacy, and of offering general encouragement to explore the discipline without fear of failure; it does not involve instructing students in a career path. At the graduate level, the most tangible qualification an MFA offers is the ability to teach; that’s the concrete obligation a teacher has to help a student to fulfil, aside from helping them to understand the professional field in which their work will be received. In either case, a major part of teaching is offering yourself and your knowledge of the field as a resource for students to use as they see fit in completing their course of study, and to later ascertain whether their use of the resources you’ve provided qualifies them for the degree or accreditation they are seeking.

There is not a set career path in art that one can rely on for guidance, that is one of the things that makes it both attractive and daunting. Being an artist forces you to figure out a way to deal with the instability of shifting receptions to your work, and the vicissitudes of the free market, both on a professional and a psychological level.

How does your work in academia and being an artist influence each other? The significance of an art practice or an art work is a question that plays out over the long-term, but the art world is constantly being buffeted by the forces of the market, which operates on a very short time horizon with little sense of memory or a stable predictable logic (at least, not a compelling one). This is not to say that the market isn’t a vital form of communication among individuals, but it is a narrow and a not particularly inclusive one. Academia (in the form of schools, scholarships, museums, etc.) counterbalances that; their rigidity provides a space for ideas at arm’s length from their monetization. Broadly speaking, I appreciate the ethical and political goals of academia, the preservation of a space for circulation and discussion of ideas. It involves a sense of stewardship and responsibility to a tradition conducted in pursuit of the common good of shared knowledge and attempts to be a meritocracy (even if it faces some systemic problems in this regard). On a personal level, moving between these spheres creates a balance, offering a place where the history of ideas and their application are paramount and protected to some degree from market forces, while having access to a space where those ideas meet the precarity and distortions of a free market system.

Do you have any rituals when it comes to your work routine? Not especially. At least none that are terribly consistent or meaningful enough to merit describing.

The art world is battling the idea of a digital show, and galleries are venturing into clicks instead of physical visitors. Do you believe there is a chance for these sorts of exhibitions to succeed even in post-pandemic days? Sure, a major part of common aesthetic experience is via online platforms, and I don’t see why this wouldn’t be a viable venue for art, since art is, in short, a discourse about aesthetics staged through aesthetics, but that’s an answer to a broader question regarding what it means to produce work for online reception specifically. On a more basic level, even before the pandemic, most of us experienced exhibitions in one or another online form, since it’s impossible to see everything one wants to see in person. I think the pandemic has given exhibition venues (whether galleries, museums, or otherwise) the impetus to make these online platforms more comprehensive and informative.

What kind of relationship do you hope the viewers will have with your work when they can only view it online? Are you worried that people will see the image but not the content? Since most of my work wasn’t consciously designed for that context, it’s hard to speculate. Material specificity is part of the logic of my work, and some of that is lost in online viewing when the work wasn’t produced specifically for that context. But there is also something gained in the wider access and the experiences digital platforms offer; the underlying question is how to make use of that potential as an artist, and how those experiences relate to the history of traditional art forms? The ubiquity of these online formats has produced meaningful challenges to my own conception of my practice, challenges I haven’t fully reconciled yet since these developments are very new. Of course, contemporary art is made with the knowledge that it will be trafficked in mediated forms, for example, through images. The awareness of art’s dependency on images has been a factor in art making for nearly a century, but digital platforms add another, much more complex layer of mediation to the mix, one that I think is only beginning to be sorted out.

You previously explored urban landscapes devoid of people. This year we saw whole cities virtually empty. Have the lockdowns made you go back to exploring that part of your work? They haven’t. That work came out of an interest in the history of representations of the city, and how that relates to the spaces created for the display of art, not an exploration of urban environments themselves. Current events haven’t inspired me to return to that work, which doesn’t mean I won’t eventually, I just haven’t felt prompted to as of yet.

I hope we are inching closer to an understanding on a societal level that the prosperity of the few has always been through the extraction of value from people and places that it treats as mere raw material to be exploited.

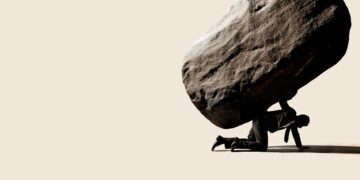

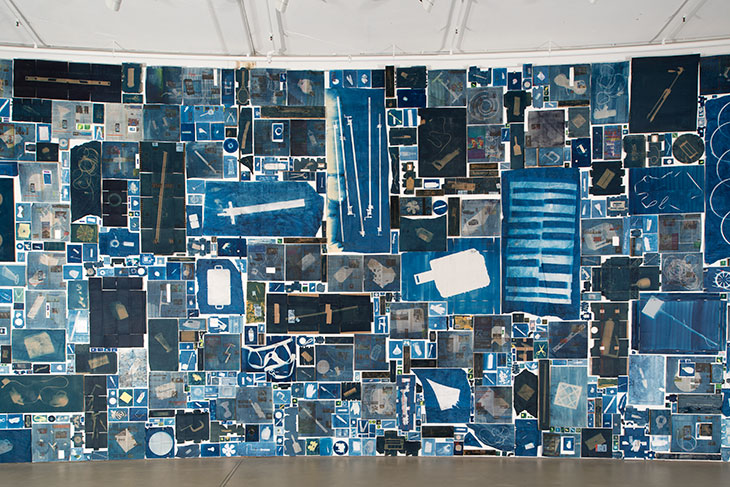

Several of your works examine, in a way, the nature of memory and damages caused throughout time. What draws you to this? I don’t think of it as damage, but rather as the accrual of use, and that use gives objects meaning. I just try to make apparent this dependence on a system that extends beyond the discrete object. Or more exactly, I rely on that system to generate the work, treat it as raw material and an automated production system without which the work, by this I also mean all art, would not exist, and try to acknowledge that all objects are dependent on a vast system of human beings not only to come into being, but to have any meaning whatsoever.

In a year where most of our lives have revolved around a delivery box, your FedEx boxes series, at least for me, has a completely different meaning. Do you believe we are close to realizing the price of globalization in today’s society? I hope we are inching closer to an understanding on a societal level that the prosperity of the few has always been through the extraction of value from people and places that it treats as mere raw material to be exploited. One of the first truly globalized and modern capital markets was chattel slavery, and most of the financial instruments we associate with contemporary global markets were first innovated by bankers and insurance brokers to enable the monetization and exchange of human beings – such as the collateralized debt obligations and mortgage-backed securities that shot to the forefront of public consciousness during the global financial crisis of 2008. The U.S. is unique in the sense that it was founded upon this newly efficient market in human beings as a fungible asset, and uniquely positioned to prosper from it. Its innovations in the financial industry revolutionized global commerce in the 20th century, but it was really a process that began in the 17th century. Art is an interesting case study in contemporary finance capital, as it has become an asset class that is particularly useful for storing and moving large sums of money around without state oversight, since it is one of the few forms of property that can be bought and sold anonymously with values that can fluctuate wildly; it makes money easier to clean, as it’s not unfathomable that a million-dollar painting might become a ten million-dollar painting in a short time span. In concrete terms, it is much easier to move or conceal a five, ten, or a hundred million-dollar painting than it is the same amount of currency, digital or otherwise. So a good portion of the art market’s recent growth is due to its utility in the contemporary global financial system, how it allows capital to flow. There is a natural tension between a humanist conception of art as a cultural product that contributes to the common good—that it inherently has a public utility and a cultural value that must be actively preserved—and its use as a financial tool. Of course, my work doesn’t have a monetary value high enough to be used in that way, and this is a phenomena localized at the very top of the market, but money from these transactions fuels the art world as a whole. I find that tension compelling to think through, although I find it much more useful to start with specifics and work outward when thinking about art, rather than to begin with a generalization like globalization or capitalism, etc., and turn that into a claim about a specific circumstance. Perhaps that is another strength that art has, it can’t operate in abstraction and generalization, it must always be realized in the specific. In other words, you can’t make a general thing, it is always a particular thing you are putting into the world.

These boxes also drew a parallel for you, between a damage a simple box endures crossing these borders and what a human body does. Yet we are playing blind to millions of refugees running for their lives to Europe. How can art speak to this present crisis? I guess some sort of analogy could be drawn, but I would never claim any objects or representations could stand in for or fully convey human experience, whether it be suffering or otherwise. Objects (here I’d include discrete yet ephemeral experiences, like performance, etc.) provide a platform for the relations among individuals, but they don’t stand in for human experience or human relations. Representation and analogy are both reductive, and the production of what are essentially a cross between luxury goods and self-reflexive aesthetic discourse can’t capture the reality of human suffering sufficiently to claim this as art’s purpose, or even one of its main attributes. It is simply not designed to do that effectively; it will always fall short if we ask it to do this. Instead I think the obligation of all producers is to focus instead on what art is good at, which is creating a community of shared experience among a group, not creating a false sense of cathartic empathy for those who are excluded from the group or the basic guarantees of the state; that requires forceful intervention on a foundational level. I find art that claims such empathic effects or misinterprets itself as a form of protest or resistance against dominant forces to be presumptuous at best, and morally reprehensible at worst.

At the moment, wherever you are on the globe, it’s hard to escape the 24/7 news cycle coming our way from the States. As somebody living in Los Angeles, how impactful do you believe the next election will be for artists working in the United States? I think that it will be impactful for people in general, both within the US and outside, and that the stakes are incredibly high. That said, I’m not sure that it will be any more significant for artists than it will be for anyone else. There are lots of people for whom it will be a matter of life and death.

As an artist living in the States, what does the American dream mean for you? Not much. I think it is a tool to justify the toil and suffering of the many, and to blame them for their own exploitation and entrapment in a system that is increasingly rigged to redistribute the proceeds of their labor into the hands of a wealthy minority with as little remuneration as possible.

Finally, what do you do outside of work and art to recharge? I find that teaching and various other forms of discussion are the most regenerative to me personally. The most peaceful I feel is when I’m trying to understand something new, and how that changes my understanding of my relationship to the world. I also like hiking, cooking, and watching TV.

Keep up with Walead Beshty’s work on petzel.com.