“Good art moves on” states our Guest Editor Natalija Pauni? in “The Haunting of” – an essay in which the promising curator reflects on how art changed her life path, and how it can allow us all to take a new course. Natalija’s story is also an essay on the possibility of prophecies through art.

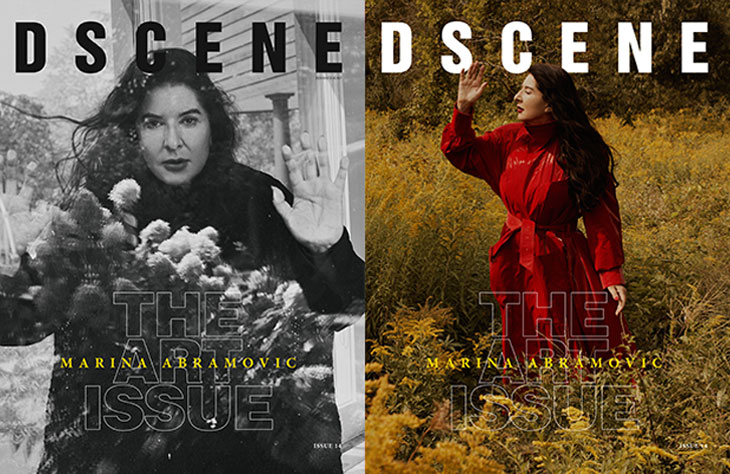

DSCENE 014 IN PRINT $12 OR DIGITAL $4.90

Read more after the jump:

THE BIG BLACK AND WHITE BILLBOARD

There is a big black-and-white billboard on top of a Coral gas station in Beirut. It says: “Like there is no tomorrow”, and it shows a tropical plant arrangement in the background. It stands by a highway, but it faces away from it so that the speeding cars and the billboard come together in the same frame to the people coming to the gas station. The year is 2016. [1]

That was the same period in which post-truth officially became Oxford’s word of the year, a word that “captured the times” [2]. We know now that some kind of tomorrow did come, but it looks like every tomorrow tangles with the words that are spoken today. It feels like tomorrows are closer to being a matter of the surreal than a matter of the possible. I don’t exactly remember when this happened, and I don’t know if it’s because of my age, or because of the age that we live in (or in Mark Fisher’s words, due to our shared lack of imagination, thanks to the confusing, saturating patterns of capitalist realism [3]), but it’s getting harder by the day, to tell what the future might be like. I began to lose sense of what information really meant because I learned to doubt it along the way. Everything sounds like a story, looks like a play, and tells me things, like an exhibition text, yet I close the part of my mind that allows me to take it in. I don’t trust it. Post-truth was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Too many lips summoning impending doom at the same time, and here we are with a global pandemic and a million conspiracy theories, ordering polyvinyl extravaganza and 30th birthday gifts via Amazon while complaining about *the wrong Amazon burning* and cracking similar funny-not-funny jokes.

Everything felt very reassuring and they told me that I was in control, however, the fact that we even discussed it made me assume that I’m not. I entered the room and as soon as the door closed, I could hear my own heart, my bloodstream, my organs. I heard my body on the inside for the first time and I entered anxiety.

Travel restrictions and so-called measures imposed by different governments, however, needed and justifiably, surely illuminated the lack of care for their citizens’ mental health. It took me a long time to see how fucked up it made me, or rather I made myself, so I chose to shift my focus in order to keep myself sane. Like there is no tomorrow and like nothing else really matters, I think about the art I like and why I like it so much (and ever since Seth Price cleared it up for me, I insist on using the word ‘like’ when referring to the sublime [4]). I like it because it’s not just contemporary; that’s not enough. I like it because it’s prophetic. Art that I like can predict, sense, and direct realities, which does not necessarily mean that the artists are aware of this. It does get out of control.

The “Like there is no tomorrow” billboard was part of a temporary art installation. The gas station was adjacent to the highway surrounding the area of the Port of Beirut. The Port of Beirut exploded in August 2020. It looked like fiction, to us who were lucky enough to not feel it real; to us who were lucky to still be there tomorrow.

THE SMALL BLACK ROOM

I guess the first time I felt the intensity of the power that art has over me was when I went to the Korean Pavilion in Venice, in 2013 [5]. There was a line in the front, people signing papers and waiting, sharing some vague excitement. The signatures were needed for the consent to enter; the visitors had to confirm that they don’t have any heart conditions, neurological disorders and that they are, generally, of good health. I was 23 and did not yet know that I was anxious. I thought I was just sad, as I’d recently broken up what I had thought was a good relationship. Or, that I was just worried about what I’d do after I complete my master’s course. So, I said I was healthy, too, and I thought I was excited.

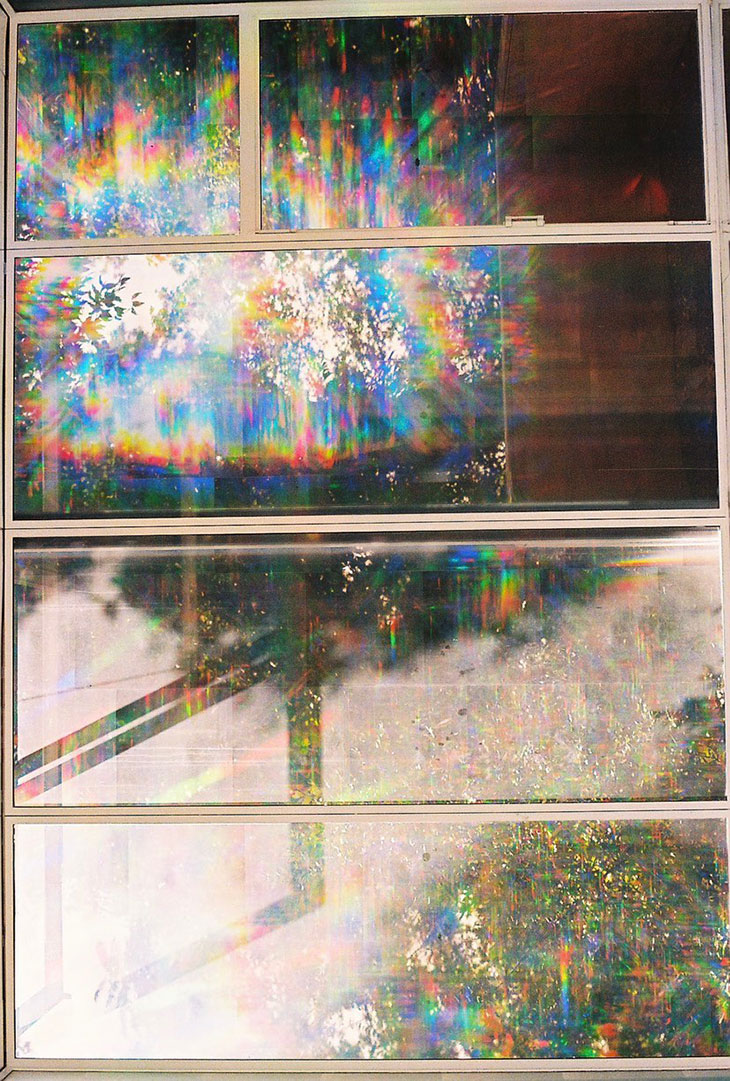

But that was not excitement. I was asked to take my shoes off before going into this beautiful, illuminated room full of mirrors and windows, immersive, heart-warming, with children running around, the sunrays breaking into colors, touching me, through some special kind of plastic. I’m a 90s city girl, I felt good in what seemed to be a high carbon footprint environment (I have no idea if it really was, but it surely did simulate nature, while being completely unnatural in experience). I loved it. But then I noticed another line, shorter, with the invigilators navigating it. These people were waiting to get into another room.

The other room was an anechoic chamber, completely devoid of light. I was told that I should try not to speak while there, because I won’t hear my voice back, and that I will be staying with a small group of others for one minute. They also advised us not to move around too much, because we would not be able to see anything. The last thing they said to me was that, should I feel the need to get out, I can simply push the door and do so. Everything felt very reassuring and they told me that I was in control, however, the fact that we even discussed it made me assume that I’m not. I entered the room and as soon as the door closed, I could hear my own heart, my bloodstream, my organs. I heard my body on the inside for the first time and I entered anxiety. I actually did want to push the door, but I was with someone I knew, and vanity is stronger than fear. Which comes to show that I was truly not in control.

My life changed. I’m not saying that Kimsooja or her installation did it alone. But the small black room surely made me do things that I would not be doing otherwise. It made me fear death on a daily basis. It made me avoid stuffy places and always face windows in rooms. It made me cry in business class and intentionally miss flights. It even made me fear space itself. I stopped looking at the sky at night, when it’s clear and the pollution is not hiding its depth, its emptiness: celestial bodies in an endless black void and me on one of the planets, forgetting about gravity and thinking I might fall off.

THE LIFE-SIZE WHITE CUBE

However, if I had not been introduced to art in this way, and had my anxiety not been set off by an art installation, I would probably be working in an architectural firm right now. Which isn’t to say that I would not be happier. But it does say that Kimsooja knew it even before me: I was going to become so anxious, that I would obsessively chase my ambition, just in case there really was no tomorrow. In a sense, she was right. It truly is black and white, but it’s both at the same time. Yin and yang, as she said herself; to breathe [6] actually also means to be out of air half the time. To live is to die a little.

The room is not actively haunting me anymore, but it does show up in other places from time to time (I could not go inside Irena Haiduk’s blind room at Documenta 14 for example, even though I tried to make myself do it many times, because it made me so curious, on so many levels [7]). Yet it did eventually point me in the direction of the white cube, however old that might sound, considering, among other things, that most of the shows I curated happened in non-standard exhibition spaces. Nonetheless, the context is always the same and I think we all know it. We come up with ideas and who knows, really, where they come from, and then we put them in a room and we get in contact with them. Most of the time, we’re not allowed to touch them (which is either explicitly written or just implied), unless it is to put them in a particular predesigned order (to install and to deinstall). But there is an exchange unwinding between me and the artwork that I’m trying to “understand”, as they sometimes say. Doesn’t that all sound like a spiritual ritual?

I used to shrug every time I heard that word, “understanding”, partly because it sounds so exclusive and partly because my own understanding was that contemporary art works at a different level and that, even if I possess the knowledge about the background of an art piece, anybody who does not, should also be able to inscribe their own reading into it. It is contemporary after all, which means that it lives within us and relates to our current temporal condition, which might be the most difficult condition to understand (the now). But now I am reconsidering my stance, because I am quite certain that, even more than I understand art, art understands me. It somehow knows so many things about me and this world, that it’s scary.

THREE KITSCH PALM TREES

I’ve recently come across something called “manifestation” and it is becoming more and more popular as the world decides to not trust science anymore. Its practitioners claim that anything can be brought about with our minds and that the only thing you have to do is believe that this is true and to set your intentions (you may have heard about this as “the law of attraction” or “assumption”). The tricky part is that these intentions don’t need to be what we consciously wish for, but they could as well be reflections of our fears and our subconscious thoughts – apparently, we are always manifesting. That made me think about all the text-based artworks I’ve seen throughout the years. Even exhibition titles. Books. Reviews. Audio guides. I really hope that there were more of the non-apocalyptic ones, that I did not get to see, or that I haven’t seen yet. Actually, you know what, I intend so.

Which brings me to this. On an unrelated note, someone told me a couple of days ago that planting palm trees in Belgrade is “kitsch”, with which I obviously disagreed but which also reminded me what kitsch is – a scheme to keep things where they are and not allow them to progress. So I remembered that art essentially allows things to take a new course, it allows us or, rather, provokes us to change – even if it means for the worse. But then, if we change for the worse, art should not get stuck dwelling on it.

Good art moves on. It has to because it takes time for it to materialize (to manifest!). And when it does, we’re already living in the tomorrow. In the immersive, heart-warming tomorrow; children running around, sunrays breaking into colors, touching me.

1The artwork is titled Like there is no tomorrow, by Ivana Ivkovic.

2 McIntyre, Lee. Post-Truth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2018.

3 Mark Fisher writes about this in Capitalist Realism (Fisher, Mark. Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative? Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2009).

4 It became “officially okay simply to like a painting”, and “enough to say, That painting is awesome, just as you’d say, That spaghetti is awesome” (Price, Seth. Fuck Seth Price.New York: Leopard, 2015).

5 The 2013 Korean pavilion in Venice was designed by Kimsooja and titled To Breathe: Bottari.

6 This refers to the title of the Korean pavilion in Venice.

7 Irena Haiduk’s work at Documenta 14 (2017) was titled Seductive Exacting Realism. It was multifaceted and consisted of different parts, but the essential bit was an audio piece that was played in a dark room.

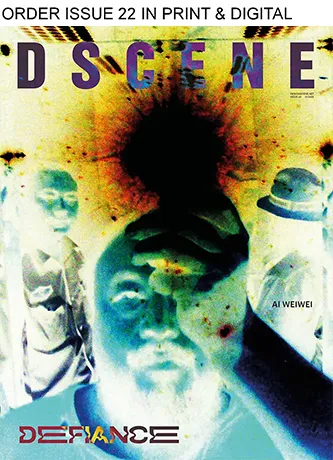

THE HAUNTING OF essay is originally published in DSCENE Winter 2020 Issue.