Contributing Writer OLIVER BASCIANO explores the story behind some of the most memorable long works by artists such as Christian Maclay, Ragnar Kjartansson and Tehching Hsieh as well as John Lenon and Yoko Ono’s famed staying in bed stunt.

DSCENE 014 IN PRINT $12 OR DIGITAL $4.90

Read more after the jump:

The average museum visitor spends just 28.63 seconds contemplating each work of art. That was the conclusion of a 2017 American study. It is perhaps no wonder then that some artists will go to extremes to hold the viewer’s attention or produce work that is too time consuming to properly comprehend, therefore one feels that they’re possibly being set up to fail (or be the butt of a joke). Take Douglas Gordon’s 1993 video installation 24 Hour Psycho which saw the Scottish artist slow down Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thriller to such an extent that the entire film, with the sound removed, is stretched out over a day. For anyone who has seen the original 1960 film, at times, the tension is unbearable: anticipating the shower scene is agonizing as actress Vera Miles painstakingly slowly meets her death. Yet this is more than a clever one-liner. As the film progresses, the viewer becomes immersed in every grimace, every flicker of fear, shock and surprise, moments one would likely miss by watching the film at normal speed. Gordon’s work in this respect is not just an exercise in slowing down a movie, but also asking us to slow down too. The fact that it is virtually impossible to watch the whole thing, conversely keeps us rooted to the spot far longer than the half minute most artworks are apparently afforded. The impossibility of the task poses a challenge, one that audiences seem only too happy to attempt, however doomed to failure they are.

Endurance art is inherently anti-capitalism, given that the main aim of capitalism is to colonise time and turn it into money, and indeed the difficulty in ‘selling’ such performances as artworks to art collectors.

The same effect is evident in another day-long artwork, Christian Marclay’s The Clock. The American artist collaged thousands of film clips, all featuring clocks or watches, or characters asking the time, syncing them in real time. Museums around the world would open their doors twenty-four hours to accommodate the work, ever since it was first premiered in 2010. If a visitor was to arrive at noon, they would be on time to see Gary Cooper in the classic western High Noon of course; at 10.04pm the lightning would strike the clock tower of the Hill Valley Courthouse in Back to The Future; by midnight The Clock would strike twelve with V for Vendetta. Then the epic work would begin all over again.

As much as it is a huge timepiece, the thousands of faces, famous or forgotten, that appear in Marclay’s work run a gamut of cinematic emotions from anxiety and joy to excitement and boredom, responses which mirror the sitting audience too, never sure at what point we should leave this movie with no ending. There is something existential, futile in putting ourselves through this marathon, yet also exhilarating and extremely moving. To call an artwork boring might seem the worst possible slander, and yet in a world where our attention span has been commodified, addled by images and marketing to hunger for the next fix, being boring becomes a radical position. The Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson actively plays with the possibilities of boredom and excitement inherent in durational artworks. A Lot of Sorrow, a collaboration with the American rock band the National, is an example of how, given the opportunity, art can provide a complex emotional experience, whilst also exposing the inherent shallowness and manipulation of the aesthetic experience. Kjartansson approached the band, requesting that they perform their 2010 song “Sorrow” repeatedly, for six hours, in front of an audience at MoMA PS1 in New York. The song is an emotional break-up ballad. “Sorrow found me when I was young / Sorrow waited, sorrow won”, it starts; the chorus lamenting “I don’t wanna get over you”. The National are a highly successful outfit, charting highly, playing world tours for months on end. On a daily basis they are called upon to perform whatever original heartbreak went into those lyrics for the benefit of a paying audience and, given that the song was a highlight of their best-selling album, will continue to do so for however long the group remains together. “Sorrow” has been packaged up and pumped out to a paying global audience hungry for sentiment. This hollowing out of emotions was performed in microcosm during A Lot of Sorrow. The initial excitement of the performance gave way to amusement at its absurdity, mixed with tedium of the repetition. Yet, as the hours ticked by, and the task began to take the strain on the musicians, the original hurt embodied in the song returned.

To call an artwork boring might seem the worst possible slander, and yet in a world where our attention span has been commodified, addled by images and marketing to be hunger for the next fix, being boring becomes a radical position.

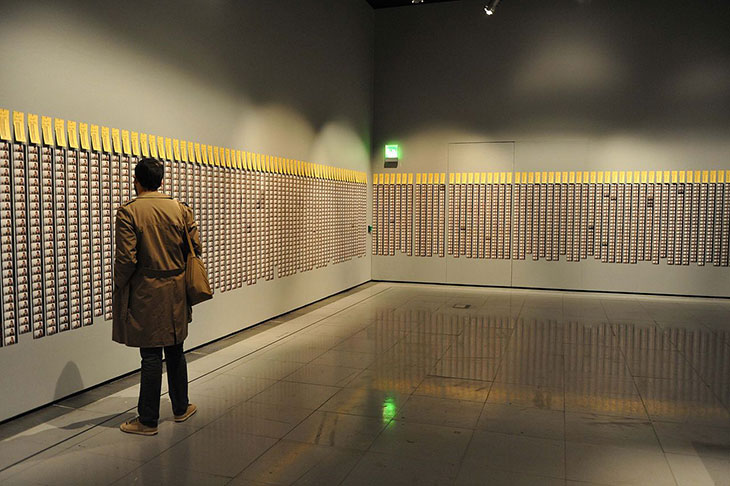

Still, all these epic works pale in comparison to the commitment Tehching Hsieh has made to his work. Matt Berninger of the National gave up one quarter of a day next to a microphone; Hsieh laid down a year of his life for art. In 1980 the Taiwan-born artist installed a time punch in his New York studio, the kind factory workers would have to use to prove they were arriving at their shift on time. On 11 April at 7 p.m. the artist clocked in, and took a photo of himself. He then proceeded to do that every hour, on the hour, every day, for the next year. Seeing thousands of these self-portraits in retrospect, the viewer is able to chart the strain that the work had on the artist, as he poses sleep deprived, always having to be within an hour of the time punch. This was also not the only grueling project Hsieh put himself through. Other year-long tests include living in a cage while in another he chained himself to a volunteer whom he had never previously met. All are a testament to the things we use to pass the time in life: whether it’s work or relationships, and how they can be both a burden, and liberation.

There is something profoundly radical in refusing to do anything for a very long time that gives the performance a life beyond the politics of that moment.

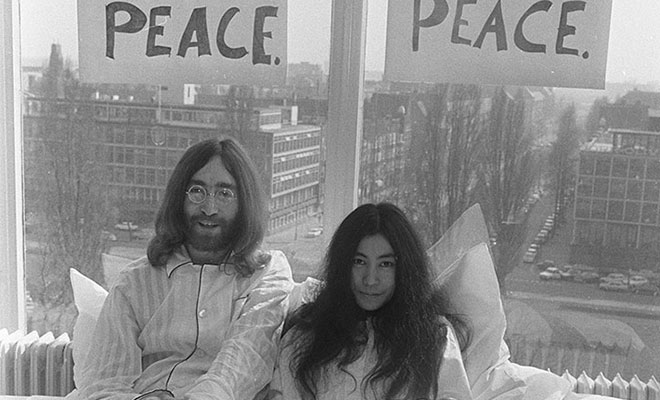

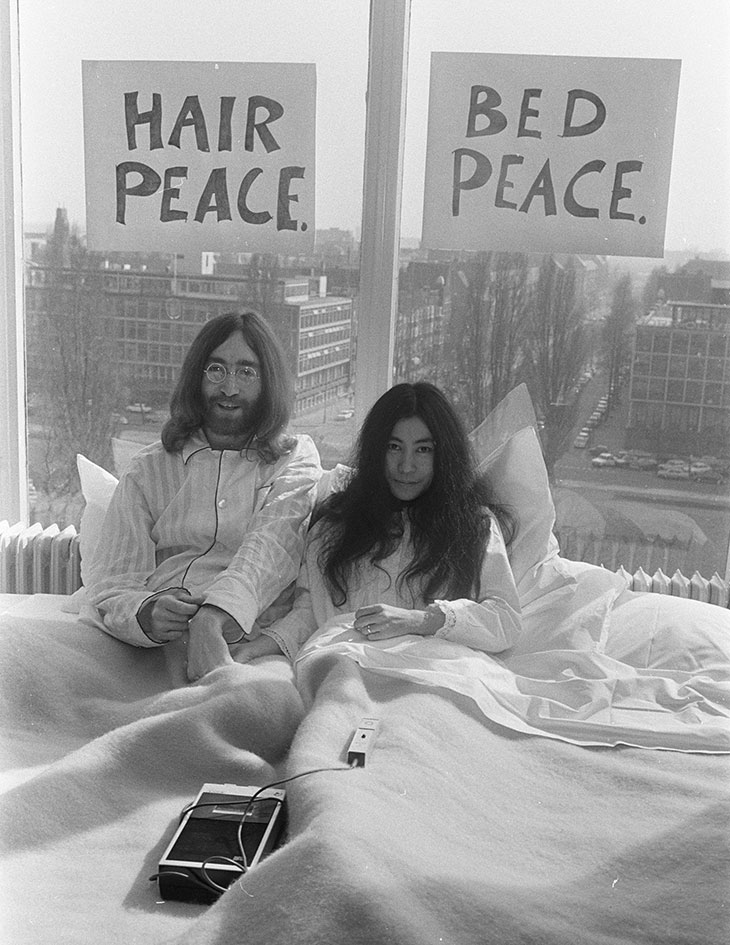

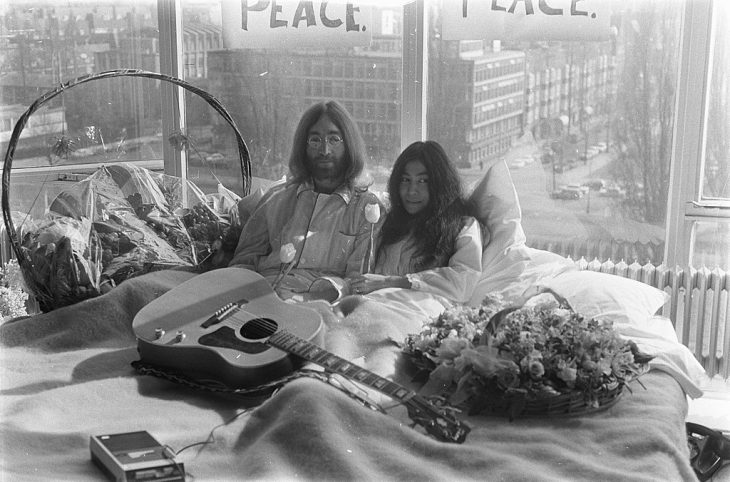

Endurance art is inherently anti-capitalistic, given that the main aim of capitalism is to colonize time and turn it into money, and indeed the difficulty is in “selling” such performances as artworks to art collectors. It was a point made by Yoko Ono when, in 1969, she and husband John Lennon went to bed for a week on two occasions. Once at the Hilton Hotel in Amsterdam and again at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal. On the surface, given the fame of Lennon and their welcoming of journalists throughout the day, these were anti-war stunts as well providing good publicity. Yet there is something profoundly radical in refusing to do anything for a very long time that gives the performance a life beyond the politics of that moment. In “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street,” an 1853 short story by Herman Melville, the titular character, an employee of a law company, stops working. When asked to do a particular task, he merely answers: “I would prefer not to,” yet continues to be at his desk promptly each day. Instead of working, he merely contemplates the wall in front of him. Like Bartleby, artists have long asked us to stop. Get off the treadmill. Eschew novelty. Take our time.

Follow Olivier Basciano on Twitter – @olibasciano