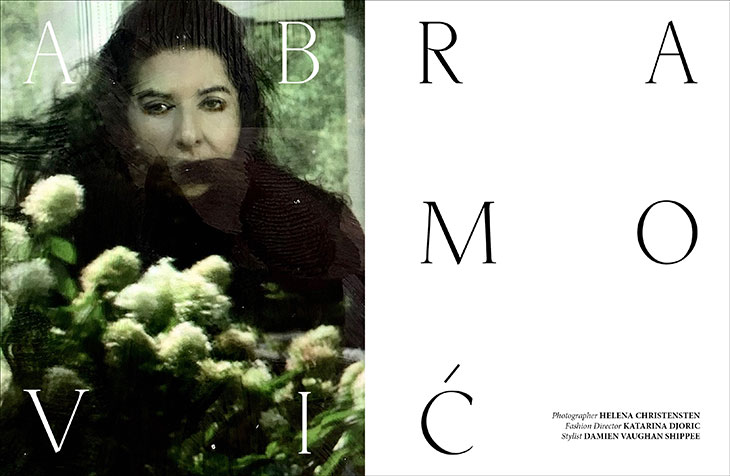

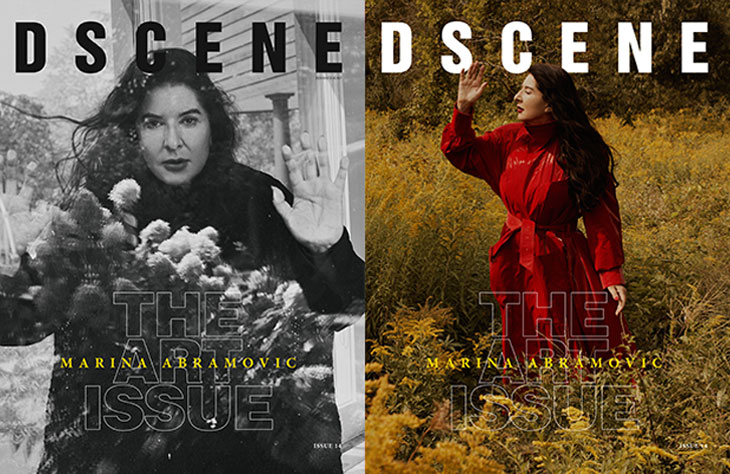

After the shoot at her Hudson home by supermodel and photographer HELENA CHRISTENSEN our cover star MARINA ABRAMOVIC sits down with Editor KATARINA DJORIC to talk about paving the road for young artists, Belgrade then and now and bringing Opera back to the front pages.

PRE-ORDER DSCENE 014 IN PRINT OR DIGITAL

Read the interview after the jump:

How does it feel being an art-world superstar? Would you say that you have achieved success?

Wow, I don’t think in those terms at all. I think it’s the public that makes you a superstar. And for me what’s much more important is for this superstardom to give me the credibility to send my message and to give me the possibility to work on larger scenes. So that finally, the performance which nobody took seriously, is taken seriously. This gave me a platform for performance art which I never had before.

Where do you draw the line between your work and your life?

There is no line [laughs]. There is really no line because you know my work and my art are always the same. Especially in my position, my body is my work. It’s the object and subject of my work. So everything is connected, I never made this division. Not yet.

Do you find it difficult to switch off?

Yes, and you know especially now in the quarantine during covid. You truly think that you actually have time for yourself but you end up with incredibly many obligations. And everyone thinks you have time. Asking you for conferences, for “Zooms”, for your opinion. You know, things like, more information about what you are doing in captivity… how the Abramovic method works…what is the suggestion for young artists? I mean, I am really bombarded by all of these questions and answers, and I feel an obligation towards them, and I end up exhausted. It’s just, you know, [switching off] in a way that I always prefer, what I’ve done before, to just escape, go to nature and then come back. But now, traveling is so unreliable so you can’t do this as easily. So my really big dream is, when this is over, to go to nature for a really long time.

I think it’s the public that makes you a superstar. And for me what’s much more important is for this superstardom to give me the credibility to send my message and to give me the possibility to work on larger scenes. So that finally, the performance which nobody took seriously, is taken seriously. This gave me a platform for performance art which I never had before.

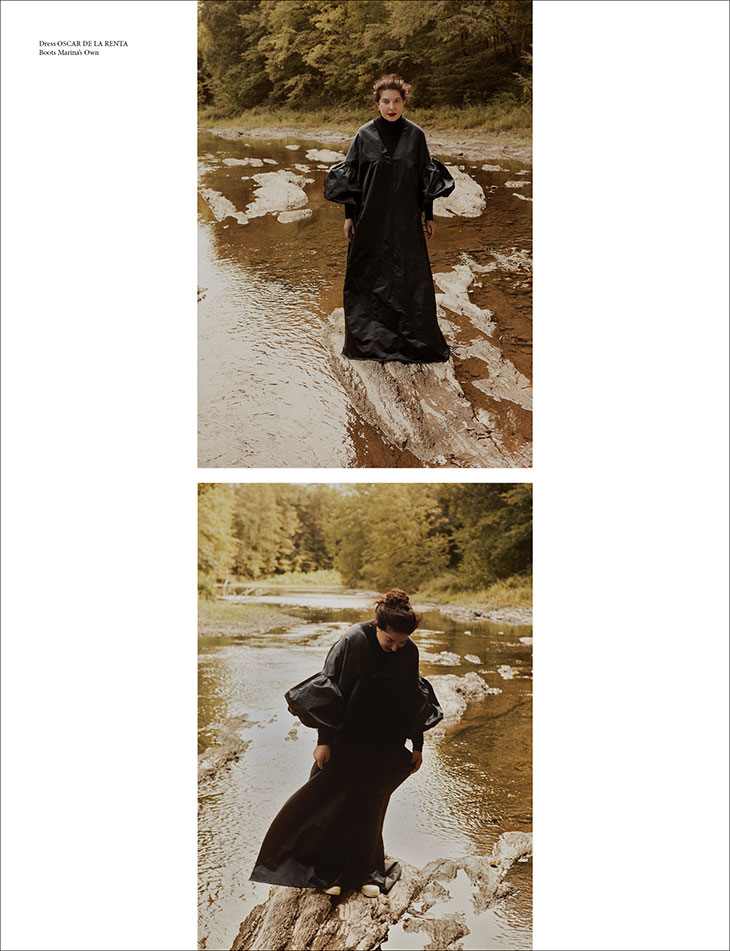

You said in one interview that working with nature fills you with energy, and working with people exhausts you.

Because nature is the first big teacher on the one hand. And on the other, it’s a generator of energy. If you just go to, what I call, places of power — waterfalls, high-tops of mountains, volcanos, oceans, running rivers; you truly feel nature’s energetic fields and then your mind is clear and ready to work. In the old days, the artists would go to the top of the mountain and stay there in solitude and meditation and would come down and make art. I think it is this kind of attitude that we should go back to, that kind of philosophy.

If we talk about the noise on the internet, do you feel comfortable talking about those conspiracy theories?

I am so happy Facebook and other social media are finally starting to take down these groups and their content. [laughs] It’s music to my ears, finally. I found myself in the middle of something that has nothing to do with me. I am such a perfect target for conspiracy theorists. Because, when they look at my work…for example, I made work with communist stars in the seventies. And now all of sudden, that’s a pentagram in their eyes and a symbol of the devil. When in Venice for the Biennale I washed bones as a comment on the wars in the Balkans, they said that was cannibalism. I even got the Golden Lion for this work…so whatever I’ve done they can translate into something else. Also, I am a public figure, therefore it’s much easier to target me with theories than other artists who are doing similar things. I sat down with the New York Times for the first time, for a very big feature, saying, “I am not a Satanist, I am an artist.” I am so tired of defending myself, because there is nothing to defend myself from really, and I hope that Trump never wins. Hopefully, these theories will just die with his leaving the office.

Nature is the first big teacher on the one hand. And on the other, it’s a generator of energy. If you just go to, what I call, places of power — waterfalls, high-tops of mountains, volcanos, oceans, running rivers; you truly feel nature’s energetic fields and then your mind is clear and ready to work.

The problem could be people not knowing enough about performance art and it’s easy for them to frame everything with a conspiracy theory, instead of reading more about it.

I am extremely disappointed with the press in Belgrade; as soon as the conspiracy theories came back—as they do with every election in the states—immediately they were saying that now Marina Abramovic is a pedophile and they gave her money for an exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art. This is such cheap press you know. Whatever they could pin on me in a negative context, in my own country, they already did. It’s not just me. Everybody who succeeds in our country is always followed by negativity. Even Djokovic, who wins all the tournaments. How?! He’s the national treasure, they should really leave him alone.

We met for the first time at the Swiss Embassy in Belgrade, at the launch of your book with psychotherapist Jeanette Fischer, and I shared a photo with you from the event. I got hundreds of QAnon comments, more than three-hundred ridiculous comments. Do you think this is some sort of a crusade against performance art? Especially if you are trying to say something deeper.

But you know social media has given them power in the United States. For Europeans, this is mostly just noise and some kind of bullshit.

How was it for you growing up in communist Yugoslavia?

I made a memoir, Walk Through Walls, talking about this period of my childhood. Talking about this Belgrade period, but also this period when everything was painted in this kind of strange green or off-white color. And the lighting at homes was always so dim, everyone was just looking so grey. There was no color. I had a sad childhood with a communist upbringing by my parents. I just remember being very lonely and unloved. For me, at the time, Belgrade was a sad place. But also, it was a very important place for me. This is where I read all the important books in my life, where I learned about classical music, this is where I really encountered art and poetry and had time to do all of this. Today it’s so hard to read a book. It’s all about googling and spending time in front of screens. Literally, I had the time to do all this reading at home, and the reality of the books became more of a reality than my own. So I lived through books, I lived through poetry. At that time in Belgrade, there were so many poets. Today you never meet somebody, who when you ask what their profession is, says they are a poet! A poet means basically homeless these days. [laughs] There is no poetry, there are no poems anymore. This was very important for me, it was a mixture of sadness and loneliness.

You’ve come back to Belgrade many times, and recently even for a massive retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Do you think Belgrade has changed?

When I came back I felt that my generation did not want to meet me. I had hardly any contact with them, they somehow disappeared and they didn’t want to confront me. Perhaps due to the success of my work, I have no idea. And on top of that, in my generation, a lot of people are just angry with me. This show at the museum had expenses, but the biggest part of the investment stayed with the museum. It was used to buy the equipment for the museum which stayed at the museum after the show. The museum was missing video screens, projectors… they were missing so many things. Now finally the government invested in all of this, that should have been there in the first place. Because of my show, other artists can use all of this, and really make the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade come alive. We also had a chance to prepare a show for the visitors, and prove that we too, can prepare a professionally installed retrospective of work. For the first time, the museum had thousands of tickets sold; there was never so much interest in the region for a museum exhibition. People came from different countries, especially from all of the Ex-Yugoslav countries. My friends joked that I am like the new Tito, bringing people together with all these buses coming in to see the show. And then, when we did the speech in front of the museum, there were more than 6500 people there. This is the first time that an opening of an art show brought such a crowd in front of the museum. It was really like an artist Woodstock, where the artist talked for two hours in front of the museum. The people were young, they understood my work and were emotionally moved by it. And this is why I did the show. I did it for young people, to give them hope. If I can do all of this at this point in my career, they can do it too.

I have to say, so many people who went to see the show—loved it, even older generations.

It was truly incredible, we actually showed what a full museum looks like. People didn’t go there; it was closed for decades. So I hope that my visit there was a good thing. Even though I felt all the pain from no acceptance by my own generation. But you can’t have everything in life.

Talking about acceptance by the industry, how has being a woman in the male-dominated art industry defined your path?

I never felt my gender was an issue, I never allowed for this to reach me. I always claimed my own territory and I am a warrior. First of all, my mother was an army major, and she ruled everything. So I never ever felt that men have more power. I took my power and I never showed vulnerability. So I really never had the experience of other women’s work not being accepted. Or that they had a problem presenting it. Whatever I wanted to do in my life, I did, without questioning anything.

My work and my art are always the same. Especially in my position, my body is my work. It’s the object and subject of my work. So everything is connected, I never made this division. Not yet.

Your latest performance piece honors one of the biggest female icons, opera singer Maria Callas. Could you tell us something more about the opera piece The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas?

We are hoping for a huge success with this piece. It is going to tour for the next two years, and I believe our local press in Belgrade never mentioned it at all! In Germany, we took the front pages of major newspapers. I am not sure anyone remembers when opera was on the front pages of newspapers. It’s always on the last pages, in the culture section. We had amazing reviews. After Germany, the performance is going to go to Naples, to Berlin, Athens, Paris…New York; it’s going to be everywhere. This is the first opera I’ve done, it’s like my baby. I put so much energy into it. And it’s really about dying from a broken heart, and it’s about dying for love. It’s centered around Maria Callas, but at the same time, the image should touch anybody who ever loved. It’s about love.

Visuals are also very powerful.

I also mixed various mediums here. Something that was never mixed before with opera in this way. The video, the film, the performance, the music by Marko Nikodijevic, who used classical and contemporary music. So everything became like an installation opera with a new concept. Very minimal in many ways. You know classical opera can go on for four or five hours. It’s boring and long, but dying is shorter, so mine is only 1 hour and 31 minutes. [laughs]

Plus, all the fashion from Riccardo made it even more amazing.

Riccardo Tisci made incredible costumes, and Willem Dafoe kills me over and over again in the piece. And then, all the opera singers we had presented different types of women. Passionate, fragile, victorious…it’s a very conceptual piece. In the end, all of our singers became one person, which is Bruna. She was Callas’ maid, who she left everything to, after her death. In the end, seven singers from the seven arias come together to clean Maria Callas’ room as seven Brunas. Tisci made their maid costumes especially for them. It was a lot of work, especially directing and starring in the show.

Talking about fashion, how much attention do you pay to trends?

Not much, because I have a great friend in Riccardo who tells me what is good for me. He’s the one who gives me the best advice. He knows my body and he knows my character. So he helps me not to be victimized by fashion. Instead, it works for me, and I feel comfortable in what I wear. I learned so much from him, and he’s not just a great friend—he never lets me down when I need to look great. When I have to give a speech, or go on a red carpet, whatever these important moments are in my life, he will advise me on how I should look and dress. I am so comfortable having him by my side.

But you had great style even before Riccardo.

You think? [laughs] You know, in the early 70s the only performance artists fashion was – off-white, off-black and naked … nude that is it. Later it became much more complicated [laughs]. But that is how it was at the time. You know, my dream is to make a performance fashion show. Maybe some change in fashion through performance art. How did all of us performance artists become so glamorous? One of the people I miss a lot is Leigh Bowery, who was creating his own style. He sadly passed away in the 90s from AIDS. He was incredible, he was such an iconic personality, especially taking on the nightlife club scene. Boy George and David Bowie were all influenced by him. You can divide all of us into inventors and the ones who follow. The one who invents things could be in any genre. It’s not inventors…I would call them originals and the ones who follow. Leigh for me was the original; I love originals.

I never felt my gender was an issue, I never allowed for this to reach me. I always claimed my own territory and I am a warrior. Whatever I wanted to do in my life, I did, without questioning anything.

Your next project is at the Royal Academy of Arts in London but has been postponed until next year.

The show is called After Life; it’s not a retrospective in any way. This one is just the highlights, not a retrospective like the Belgrade one. This show is almost fully prepared. With having to wait one more year, this will be the most organized show of my life. [laughs] I am also the first woman in the 150 years of the Royal Academy to have a solo show. This, I feel, is the most important part.

Do you find it challenging for that reason?

Yes, and I really want to pave the way for other women after me. I feel like a tractor, going in first, and breaking down the walls for other women coming after me.

You are now facing delays in the exhibition, and also other artists can’t perform anymore. Do you think the art scene can survive the pandemic?

You know the black plague lasted over fifteen years, millions of people died. But after all that time, life continued, and now we have all this technology so hopefully, we will find the cure much faster. And life will continue; and the performance will never die. Performance is like a phoenix, always coming back from the ashes. It will survive. I don’t want to compromise. And do these “Zoom performances”. I find them really boring and with a bad image, bad quality, and the sound is honestly not good. You can’t truly replace something that is life. And performance is life, it’s a live experience. So no compromise with that for me.

You said that you have a happy day, every day, so do you live a happy life?

You know, I’ve had a difficult life with ups and downs. And not easy, many times with a lot of drama. But right now, next month, I turn 74, and I have never been as happy. I wake up with a smile on my face and say, oh my god, another wonderful day, and I am alive. So, I really think that happiness comes with wisdom.

Is there anything else that you would be able to do except art?

Wooow! [laughs] No, I don’t know how to do anything else. [laughs] I have been doing this for half a century. But one of my big dreams would be to have a nice voice. If I could ever be born again I would love to also have a great voice. I would love to be able to sing and have a voice. This is something that I truly long for.

What else would you like to be able to do, except sing?

Oh, real estate! I would love it. Flipping old houses and making them entirely different.

Are there any small, seemingly unimportant things, you secretly enjoy doing?

Oh my god ha-ha, watching bad TV and eating chocolate full of milk and butter. Having fun with my friends, trying out the clothes that don’t fit. Taking on a diet and then not following through the next day. Oh my god, so many things. Telling dirty jokes and also making fun of myself. You know that is very important.

And finally, when are you going back to Belgrade?

I love coming back to Belgrade incognito, I think I will get a wig for my next trip. I love doing my things in Belgrade, I love one of the hotels downtown. I love their coffee, going to the local church. Love to walk to the fortress. But I honestly don’t want to be recognized next time. I would really love to enjoy all of this without anyone recognizing me.

PRE-ORDER DSCENE 014 IN PRINT OR DIGITAL

Photographer HELENA CHRISTENSEN at Unsigned Group – @helenachristensen

Talent MARINA ABRAMOVIC – mai.art

Fashion Director KATARINA DJORIC – @katarina.djoric

Stylist DAMIEN VAUGHAN SHIPPEE – @damienvaughanshippee

Hair Stylist YUKIKO TAJIMA at See Management – @yukikotajima

Makeup Artist ROMMY NAJOR – @rommynajor

Producer SHERI CHIU – @sheri.chiu

Photographer Assistant CESAR BALCAZAR – @cesarbalcazar

Post Production IGOR CVORO – @igorcvoro

Comments 1