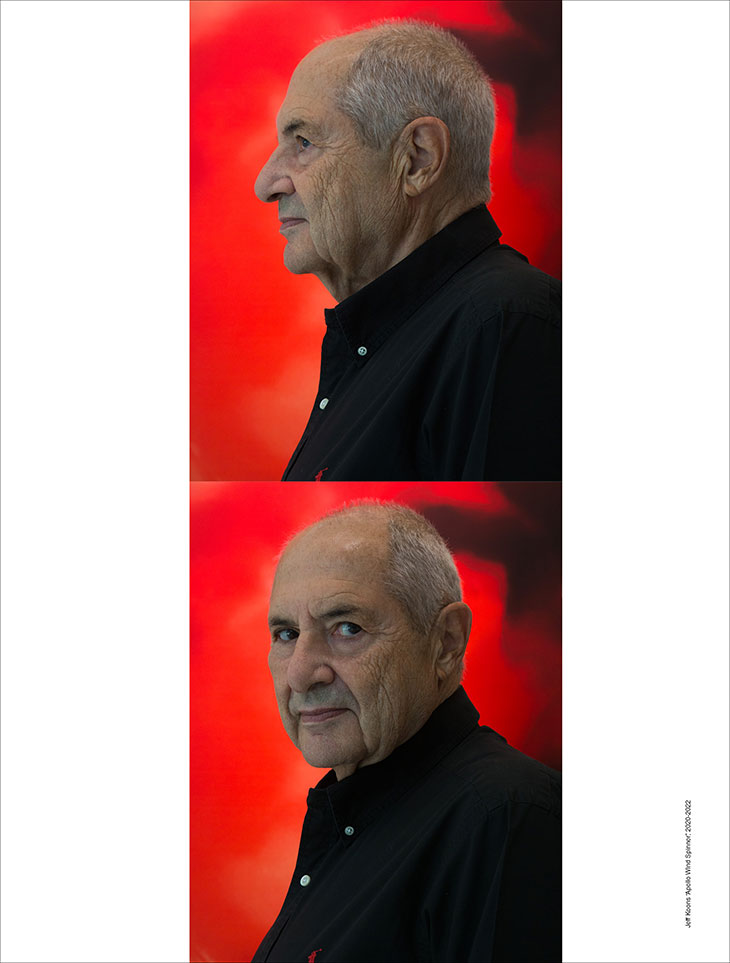

Greek entrepreneur and renowned art collector, DAKIS JOANNOU, fell in love with art at a very early age. Flash forward to 2022, Dakis is considered one of the preeminent collectors of contemporary art in the world. His art collection, which is currently among the best in the world, is motivated by his friendships with artists, many of which are spanning over several decades. Through the DESTE Foundation, he is committed to promoting ideas, and creating a platform for new, up-and coming artists. Dakis supports the artists whose works he buys, and his collection is an expression of the connections he has made. Additionally, the collection of artworks has become incredibly well-liked and in high demand from other museums, organizations, and young collections including MoMA and Documenta.

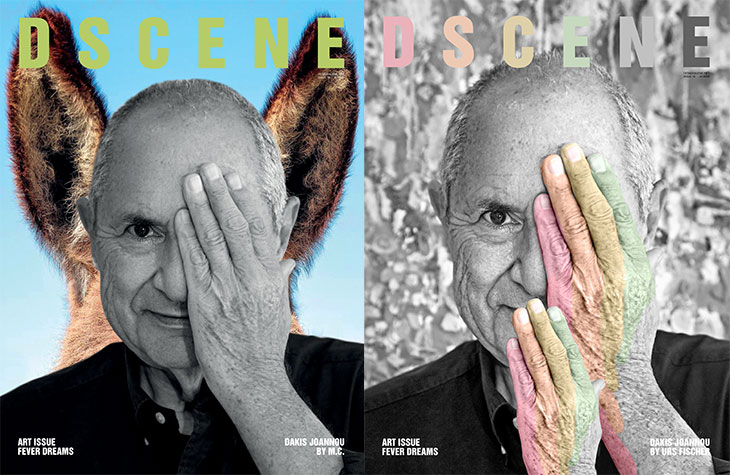

GET YOUR COPY OF DSCENE “FEVER DREAMS” ART ISSUE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

Art editor VUK CUK sat down with Dakis to talk about his love for contemporary art, the friendships he made along the way and the upcoming 40th anniversary of his DESTE Foundation.

it was the first week of July when our team of editors came to the preopening of hotel Nous in Santorini. We arrived in the late afternoon, and I remember that the first thing that struck me was the vast view of the sunset from the hotel garden and the magic gradient in the sky—spanning from fiery orange to deep blue, interrupted only by the tall palm trees piercing the skies. After entering the lobby, I immediately saw works of Eva Papamargariti hanging there – an artist whose works were exhibited as a solo presentation at the Liste Art Fair just a few weeks before—a presentation that really occupied my memory in the weeks after. After seeing her work there, I remember having a feeling that everything was weirdly connected, a situation I would more often experience in a dream than in real life. It was even more emphasized by the emptiness of this huge space since it was not yet open to the public. Afterward, while being escorted to our room, I noticed a lot of emerging and talked about Greek artists’ works being smartly positioned all over the hotel. Even the rooms had original pieces. Unfortunately, high-end hotels do not often feature young artists who push boundaries and explore new things in the art realm, so I was instantly intrigued to know who is behind this place. As it turns out, it’s one of the biggest contemporary art collectors in the world—Dakis Joannou. We immediately inquired about an interview with him, and we were thrilled when he agreed to host us at his home in Athens in late September.

Joannou opened the door and welcomed us with a big smile on his face, taking us downstairs to the gallery inside of his home straight away. We found ourselves in the big space full of natural light coming from the roof windows. It was filled with artworks of artists such as Maurizio Cattelan, Paul McCarthy, Jeff Koons, Kaari Upson, and Urs Fischer—among others. We roamed the connecting rooms while he patiently explained the story behind every work in there. Straight away it was obvious how passionate Dakis was about his collection.

Before our visit to his home, we went to see the exhibition of Kaari Upson at the DESTE Foundation—an exhibition space founded and owned by Dakis. The show Never Enough pays tribute to the late artist’s body of work. Dakis curated the show as a kind of homage to Kaari, who was his close friend. Impressive selection of thirty pieces was displayed – encapsulating her entire career, from the photograph It’s Never Enough captured in 2007 to her final works, as well as an untitled painting on canvas completed in 2021. We instantly started talking about Kaari’s work we saw at DESTE in Athens, but also in his home. “I wanted to articulate my feelings for Kaari” he said “and not go to a curator to make a show about her. It’s a very personal thing to me.” What struck me the most was the contrast between monumental sculptures and highly detailed large-scale drawings, it was one of those shows that you can observe as a whole, but also you could come closer and examine the richness of the details in each work. The sense of closeness between the artist and the curator was hovering all over the room.

We finished the tour of the collection at Dakis’s house and climbed the stairs to the living room where the story of his impressive art collection extends. We were surrounded by artworks of George Condo, Jeff Koons, and Urs Fischer, all accompanied by the 60’s furniture he is also passionate about collecting. This house was all about the art and design and showcasing it. “Before, I had Art Deco pieces which are great pieces, of course. In June 2004, during the opening of the exhibition of the Collection “Monument to Now”, I realized that this furniture had been widely popular. The house was completely redone with the 60’s Radical Design furniture by Christmas of the same year.” Joannou’s interest in art started at an early age. He had posters of Picasso and Modigliani hanging on the walls of his room. As a graduation gift he asked his parents for artwork from Lucio Del Pezzo. As he explains, his love for art was neither learned nor started; it was an interest that was expressed in many different ways. “From doing things like “the Cokepipe thing” [a sculpture that he made as a young man] to collecting, to having the DESTE Foundation, doing a fashion collection,” says Dakis. “I always had to have an angle that was not really what was expected or fashionable, or popular. There’s always a unique angle with everything. It is very important for me.”

Unique angle is also something that defines an artist’s approach to their work. I wondered if Joannou ever considered becoming an artist himself. “You have to have a commitment, and you have to have the talent to become an artist. I have neither. So, I could not become an artist,” he says. He did, however, create a sculpture as a young man— a pipe on top of a Coke bottle. It is a recreation of the original piece.“I took one of my pipes, found an old Coca-Cola bottle, and gave it to Urs Fischer to organize the multiple fabrications.” For his 75th birthday, Joannou made 500 copies and sent them to all his friends. Instead of receiving presents, he sent them all his art. “I like to turn things around” he explains. The big version stood in the garden right behind us. It was made in Carrara, in a place called the “Michelangelo quarry.” He went there at the urging of Maurizio Cattelan when he was doing some work on marble. He asked for a Coke bottle to be his own height. “It is a Duchamp pipe, not a Magritte.”As he puts it, “It’s a Duchamp-meets-Warhol.” He made a few more things but threw them all away. “Sometimes I post some of my drawings on IG without saying who did them, just to see people’s reactions. A lot of them ask who the author is [laughs].”

“Good art is good art wherever it comes from. So, we had a system with the DESTE Prize, where we had local curators and art people choose artists. That’s how I see our role in Greek art—we create a platform for the artists and let them go on with their own strengths.”

We continued the conversation talking about the rise in the presence of Greek artists in the global contemporary art scene. Today’s Greek contemporary art scene is very diverse, with many new spaces and galleries opening up. Art Basel Online recently published an article about it. Documenta 14, for the first time in its 62-year-history, happened outside Kassel and came to Athens. The Athens Biennale also had a really good echo in the art world.

Joannou started the DESTE Foundation in 1983 with the idea of promoting emerging artists alongside already-established ones and encouraging dialogue about the connection between contemporary art and culture. DESTE means “look,” so I was wondering how significant this role (and the role of the foundation) was in turning the spotlight on Greece. Joannou says, however, that they never wanted to “support” Greek art specifically because they don’t believe in nationalizing art. “Good art is good art wherever it comes from,” says Joannou. They had a system with the DESTE Prize, where the local curators and art people chose artists. “There would be a jury of museum directors and artists from abroad who would interview the artists, look at their art and choose the winner. That was a way to create a platform for the artists to step on and do whatever they could. This continued for twenty years, but then Greece had already started getting more international attention, because we achieved our original goal,” says Dakis.

Then there were two big shows with the New Museum. “Their curators would come and do the shows: The Same River Twice and The Equilibrists, which was a really successful project. As they happened at the same time as Hydra openings, the international crowd came, and they could see thirty or forty artists chosen by the independent people who had time to do the research. In fact, for the first one, Gary Carrion-Murayari, one of the curators, visited more than a hundred studios, from Athens to London and Germany, Cyprus to Thessaloniki. Many of these artists were picked up by galleries,” he says. That’s how Joannou sees their role in Greek art—they create a platform for the artists and let them go on with their own strengths.

With DESTE’s 40th anniversary next year, Joannou reflects on his impression of what he created. “What is stuck in my mind, and what is still with me, is the flexibility we have. We decide on a show, maybe we start installing it, and in the meanwhile, the show changes. Maurizio, Massimiliano, Urs, Jeffrey, Ali have been involved in the installation of many shows moving and changing things around. It’s this kind of flexibility of being able to “play” in a friendly and natural way. This is what we have been doing the whole time, which I find truly rewarding.”

Hydra, on the other hand, is a different story. It is a deliberately low-budget project challenging already successful artists. With Jeff Koons’s show happening at the time, I noticed the show, with its monumental sculptures, and site specific character was not exactly low-budget. “It was not, but that was up to him. I didn’t know what Jeff was doing since he made all my collaborators for this show sign an NDA, so I wouldn’t know what was happening. He gave me the joy of a first impression!”

“A relationship, for me, is what is most important. All the artists that I collect are also very close friends of mine. I remember we had a discussion with a guy working with the British Museum, and I told him about this. This very English, smart guy told me I should try to look at the art without knowing the artist. I told him, “Then I should be collecting Monet”

The story about how Joannou started is well known in the art world. He saw Jeff’s One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank while he was still a young artist. Intrigued, he put it on hold and asked to meet and talk to the artist before buying it. I wanted to know what the conversation was about. “We spent two or three hours together. We exchanged ideas and talked, and I just had this feeling that I was talking to someone who was an extraordinary person with immense talent. I had more than a feeling about him. It was an understanding. And when it comes to relationships with artists, it’s not about talking about specific work, explaining it, or trying to understand it. It’s about meeting with them, exchanging ideas, having a few drinks, having dinner, and communicating,” Joannou says. This, and many other encounters, made Jeff change his views on collectors. Joannou broke down barriers that he always thought he should have with collectors. And this is the type of relationship Joannou strives to maintain with most artists—a close friendship.

This kind of instant-friendship is not always the case. He explained how sometimes the situation is completely opposite. “I would acquire a piece before meeting the artist, and after meeting them you may realize that the work does not have the depth you expected.” His collection boasts more than 1500 works. Each piece was hand-picked by Dakis. When asked about how he chooses the works, he explains it by calling it “the web that connects it all in my mind.” It’s not a theoretical, conceptual collection. It is something that “connects unconnected things. The Collection is about art and life.”

For Dakis the collection can be like a walk down memory lane. It brings back the circumstances, relationships, and the time it happened. “In general, art is a perfect way to define an era—provided that a particular artwork has longevity. You can see it after a hundred years because fashion also defines periods of time,”says Dakis. “But fashion is, by definition, ephemeral. There are a few pieces, of course, that became iconic. But fashion is made to change every six months. Art is not. Although, now it seems like it has become a little bit like that. Fashionable art. The first time I heard about such a thing, my hair stood on end. How can you talk about fashionable art?”

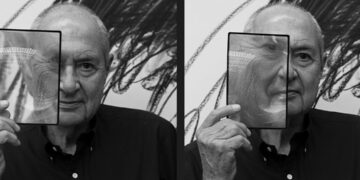

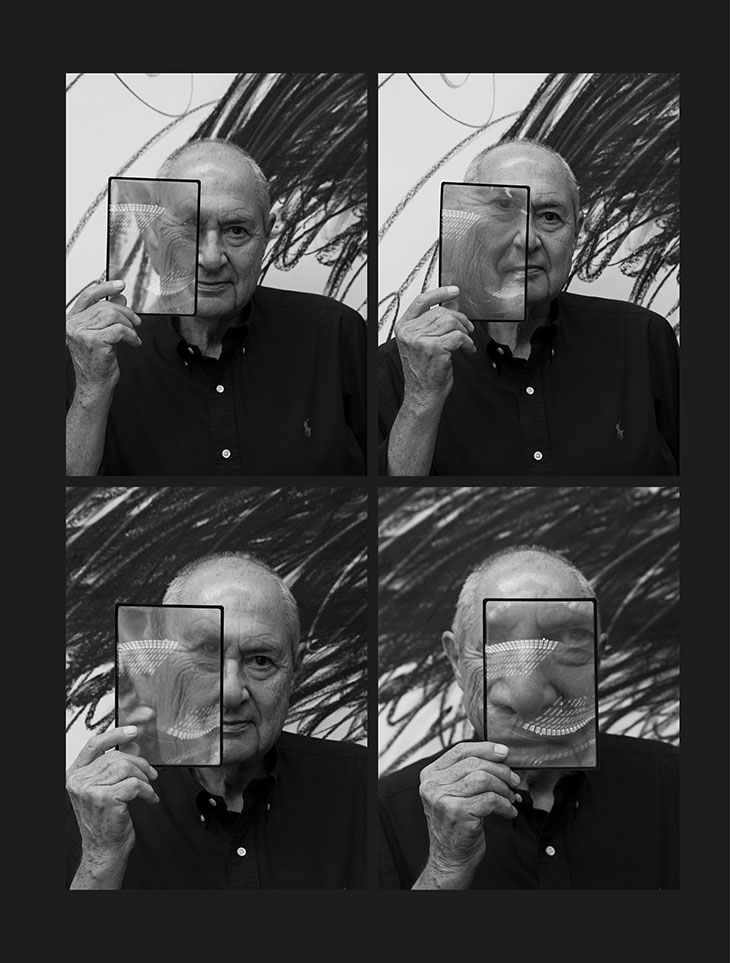

There seems to be a narrative inside a narrative—Joannou’s portraits inside the collection. “I did not commission them; they just kind of happened,” he says. “Like with Roberto Cuoghi. I just wanted to get a piece from him. He was (and still is) doing very little work.” They met at his studio, and the artist decided he wanted to do a portrait. In that piece (Megas Dakis by Italian artist Roberto Cuoghi), there is a hidden Assyrian demon Pazuzu. Pazuzu is a wind demon that protects people’s homes from other wind demons. “He’s a good Demon” Dakis said. A big sculpture of this demon is also installed in the forest of his estate in Corfu accompanied by an incredible installation with music that Roberto created.

The Collection gives the impression that Joannou never pushes an artist in a specific direction. He is always interested in total freedom of expression. “Once you start putting your ideas in, you begin to compromise the artist’s work. That’s why I do not commission a work.” This is not always the case with art collectors. When asked if he considers his collection a financial investment, he said, “I will answer you differently. One person was trying to be critical about my collection and asked me, ‘’Why do you always get trophies?’’ My answer was, “I never bought a single trophy; they all became trophies afterwards.” Sitting there surrounded by what became trophies, something caught my eye. It’s a photograph of Dakis in front of a sign that says, “LIFE WITHOUT ART IS STUPID.” I asked why and he answered with a question “I am wondering that myself [laughs]. Maybe you have the answer?”

One person was trying to be critical about my collection and asked me, ‘’Why do you always get trophies?’’ My answer was, “I never bought a single trophy; they all became trophies afterwards.”

The collector also applies this rule inside of hotels that he owns – New Hotel and Semiramis in Athens, Nous in Santorini. From the first moment you enter any of them, throughout you are always exposed to art. I was curious if he was trying to immerse guests into the same experience he has every day at his home. “I don’t know. Each visitor comes with their own plan. To have some fun, do business, to holiday, or whatever. We surround them with art to give them a stimulus. That’s all. You don’t want to be oppressive and force someone going to Santorini to swim to think about art. The art is there; it’s up to them to engage or not. Its purpose is really to be there. Whoever feels like enjoying it can. Whoever feels like just walking by can do that too.”

I asked him if art can change the world. “This is its role. Of course, it can,” he says. I wanted to know how and he replied “That’s a good question… I have no idea!” As someone who has been passionately collecting art for the past 30 years I was interested if he is still excited about it as he was when he started. “Now I am more excited about seeing people I am already connected with and their progress and new work, rather than struggling to discover new artists, although I always keep my eyes open.”

We had the same question for everyone in this issue—What are your dreams for the future? “I am not sure that art is about dreaming. Art is about life and living it,” says Dakis. But dreams are part of life. “Part of sleep.”You can daydream and have dreams about the future—in terms of ambition. That’s why it’s such an interesting term because it can be many things. “And that’s why I am avoiding it [laughs],” he says. I guess we just have to wait and see.

The next day, we woke up early to catch the first-morning ferry to Hydra. It was going to be one of the last summer days, we were told. Dakis invited us to his super-yacht named Guilty, probably the most talked about vessel in the art circles. It was designed by Jeff Koons and an Italian yacht designer Ivana Porfiri. We had no problem finding it in the harbor, and we were again welcomed with big smiles by Dakis and his wife, Lietta. We had coffee and homemade cake served on a plate with “PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT” inscribed on it – I related. The boat was also filled with art and uniquely designed furniture; we were not surprised. We chatted about art, fashion, new technologies, and the world we live in today. I remember feeling that he could go on forever when it came to art and specific pieces we discussed. I took one napkin with the “Guilty” logo as a souvenir. I. tried to be discreet about it, but I think he noticed.

Afterwards we went on to see Jeff Koons: Apollo, a solo exhibition on view at DESTE’s Project Space at the old Slaughterhouse we talked about the day before. The first thing you see when you walk towards it is a huge sun-shaped wind spinner placed on top of the structure. It has Apollo’s face on it. Within the Slaughterhouse is the 2.3-meter-tall painted sculpture Apollo Kithara surrounded by murals that refer to ancient frescoes from Boscoreale, near Pompeii, and a floor that is completely covered in mosaics. Elements that correspond to this installation, ranging from burning candles and sage, music playing in the background, a bronze pair of Nikes, and a reflective ball placed on the balcony in contrast to the uninterrupted view of the sea, made me think how much can be said in such a small and restricting space. The cherry on top was a highly realistic kinetic sculpture of a python wrapping around Apollo’s legs. It was both funny and intimidating at the same time. It broke down a couple of times during the course of the show, we were told by DESTE staff. Technicians from LA had to fly in to fix it. It’s such a unique exhibition space with an unexpected show inside. I heard some rumours that the wind-spinner-sun might permanently stay on top of the Slaughterhouse since it already became a Hydra landmark. But shh, it’s still a rumour.

We had our day on the beach and returned to the harbor to catch the last ferry. While we were sailing out, I was watching the landscape from the upper deck. Although the boat was going fast, everything around me gave me a strange sense of calmness. Passing through islands, watching many of them unpopulated and very small, got me thinking about the last three days, and suddenly I realized—this whole project started with the sunset and is now ending with one. Although I wasn’t sleeping, the entire situation got me daydreaming about the future—with the wind in my hair and the sun going down on the horizon, making this memory all orange and blue.

Photography IGOR CVORO – @igorcvoro

Realisation KATARINA DORIC – @katarina.djoric

Interview VUK CUK – @vukcar

Cover Artworks – MAURIZIO CATTELAN and URS FISCHER – @mauriziocattelan / @chaosursfischer