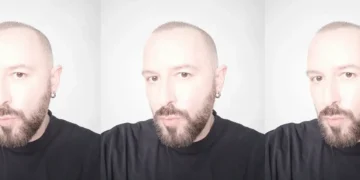

Photography by Oliver Matich

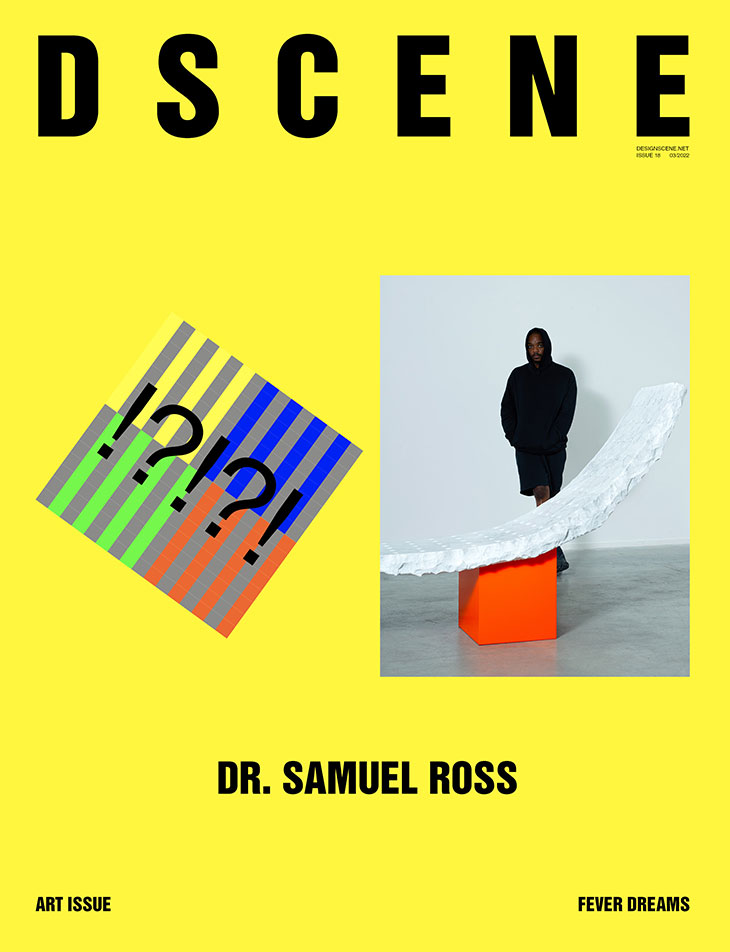

A visionary artist and multidisciplinary talent DR. SAMUEL ROSS is part of a new wave of creatives constantly pushing the limits in fashion and design. Curious and exploratory, he is constantly redefining our understanding of art, design, fashion and luxury.

GET YOUR COPY OF DSCENE “FEVER DREAMS” ART ISSUE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

DSCENE Magazine Fashion Director KATARINA DORIC sits down with Ross to talk about his childhood dreams, A-COLD-WALL* and our responsibilities towards the planet but also social equality and his DSCENE cover design.

Hi Samuel, are you in London now? — Yes, I’m in London, in 180 The Strand, where we have been based for four years now. It’s become this incredible microcosm of very brilliant artists and startups. We have two spaces here on the fourth floor. We have A-COLD-WALL*, with a team of around 25, and the one where I am at, the SrA office, and there’s like only two chairs. It’s very different energies between the two.

As our art issue is about dreams, let’s start with dreams. What was your childhood dream? Did you always want to make things? — My childhood dreams are connected to my childhood memories. You know how the two kind of interlope and overlap. It is interesting that when you look back at a dream, it’s almost like a crystallized state of memory that captures what the dream was. So a dream is not really a dream, but it’s a memory. My earliest memories and the most structured memories are how I spent so much time on my own as I was homeschooled. You get to know yourself and the idea of self as you spend so much time on your own. I was an only child until I was seven and a half, so my earliest memories are those of solitude and spending time making things, drawing, painting, and building using paper and craft materials. My parents kind of shaped me to be an artist, I’d say, so that behavior was what was always rewarded. So, from quite a young age, the idea of artist identity and being a maker was something that was celebrated, so I always knew that I wanted to create because my earliest endorphin release was from making or creating.

You studied graphic design and illustration and then switched to product design. But how did you discover fashion? — I think fashion was always a thread. Now, back to the dream part, my earliest memories were actually making life-size paper sculptures of people. Shaping a body with materials has always been there, even before graphics. I was more of an illustrator and a painter. I did graphics because I thought it would be more of a responsible choice for a career. Clothing and its relationship with fashion—I really didn’t know it as fashion. I knew it as style, as a product, as a garment; I knew it as a uniform. And there was always an opinion on material and wanting to have something which was a little bit more articulate with a different textile and a specific take on color and fabric. It became fashion very late on for me. The word fashion was maybe introduced to me at the age of 17 or 18. Up until that point, it was just style and product. So the move to product design always seemed quite logical.

“My earliest memories were actually making life-size paper sculptures of people. Shaping a body with materials has always been there, even before graphics. I was more of an illustrator and a painter.”

— Dr. Samuel Ross

The late Virgil Abloh played a key role in your career. How did the collaboration come about? — Yeah, I was Virgil’s assistant first and foremost. I first met him in quite a formal way. He reached out to me on my website, which he came across on my social media. I liked some of his photos, and he went on my page and liked mine. He then emailed me and saw a mature body of work there. I was already within the design industry at that point, and of course, I knew of Virgil’s work. I was already trying to outreach him prior. So, the serendipity and timing just aligned. I left my job instantly and became his assistant. First, it was an internship, but soon I became a paid member of his team, his first design assistant. There were no borders or barriers to what we worked on. We worked with sound, stage, light, sculpture, and physical installations. It would be a label for Kanye [West] APC or for Donda. It would be stage design for incredible artists, Off-White graphics, and runway developments. There was no stopping what we believed we could achieve at that point. It was a very special time.

It sounds fun, but it also must be exhausting, working on so many things simultaneously. — I think it didn’t seem like it was a difficulty. I think at that point, the idea of multidisciplinary design started to come back. If you think of mid-century designers like Massimo Vignelli, Seymour Chwast, or other black design heroes, they all followed a similar vernacular and path. People like me, who went to art or design schools, studied these incredible individuals, and we didn’t understand why design culture was regressing in the mid-2000s to return to a person becoming a specialist versus a pluralist. We deeply believed in the idea of pluralism. I think a lot of that was underpinned by technology. If you think about Adobe C Suite, Rhino, and Logic Pro, we didn’t understand why we would only ascribe to one application when we can use 14 different applications. That affected the way we produce. We used Dreamweaver, as well as Adobe After Effects and Final Cut, and we didn’t understand why we wouldn’t go and pick up an EOS 5D camera and buy a 135mm lens and go and capture and edit in sequence and score the piece of cinema. We didn’t understand why we wouldn’t do that. It was actually very liberating.

But do you think that creativity suffers with that many tools? — No, I think at that point, it was a very interesting format in which Virgil was working and, by nature, how Donda was working. There were only a few of us.

You kind of created a movement. — Yes, I think that way of working was new for our generation—across Millennial and Gen X at that point. Again, the Boomers had already done that. The names I previously mentioned have already done it. But for us, it was a new way of working. I was with a client who is part of a huge vehicle group based in the UK, and they were kind of saying, “You guys took design over the last 5-10 years; you just took it and brought out this newness and added this BIM to it.” And I remember leaving product design, and I thought this was too slow. It’s not moving as fast as the internet is moving, as the zeitgeist is moving, and that’s why I actually moved from product and graphic design into fashion, as well. It was part of that; the world was moving quicker than the industry was.

Yes, but it’s still connected to your approach to product design, fashion design, and all other disciplines. I think your work always has something in common. — Yes, completely. As I always say in my lectures, that plurality and multidisciplinary approach to graphic design is still the swipe card and swipe key to understanding semantics and semiotics, proportion, and textualization. That is where one should start.

Let’s talk about A-COLD-WALL*. You started your brand in London, moved it to Milan, and now I hear you’re planning a runway show in Paris. What part does a city play in your creative process? — So much of the brand’s narrative is based on social and geographic connotations and talking points in architecture, modernist environments, and experiences. It gives A-COLD-WALL* this autonomy to be able to move from city to city and to respond to the energy of a city. When we started showing in London, 2015-2017, everything was happening here. Denim Tears was born here, so much of what Virgil was working on was recorded here, and No Vacancy In was born here. Grace Wales Bonner, a dear friend of mine, had just shown her CSM collection in London. Craig Green had shown the year before. As time moved on a bit towards 2018 and 2019, my approach to style started to formalize and mature. And when one thinks about that, Milan is, of course, the epicenter of traditional European menswear. It made sense for the brand to learn that way of behaving with a maturing audience. And with myself as well, as I became a father at this point. It gave me a different perspective on styling as well. My idea was beginning to reshape, I was splitting “self” from the company, and the company was becoming more of an entity than a persona. After we showed our collection in Milan, the world turned around, and we went directly into lockdown.

Yes, I was there at your first show in Milan, and I thought this was what Milan needed, something new and fresh, a different perspective, and then the world shut down. — Just like that, the world shut down, and we had to shift. When the world woke up again, I spent about a month between Cupertino, Boston, and New York. Being around the creative community again, East Coast and West Coast, and hearing how people felt about Europe, the only city you would hear about is Paris, and again that is what the zeitgeist was. Through private installations, we released the piece of footwear with Converse and did an after-party. Then we did a rave with Dr. Martens. This idea of preemptying the ground before loading in for the January runway was very important for us, ensuring the brand was preset before going in to show a body of directional work.

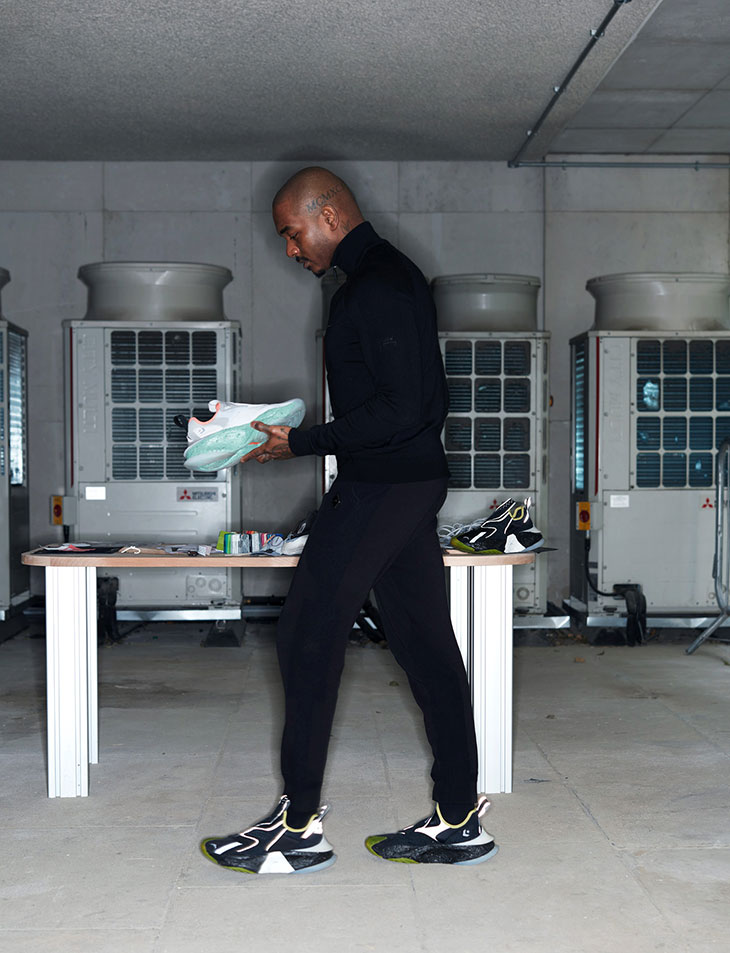

Collaborations are very important for your brand and most brands today. Why is that? Is it particularly useful to exchange opinions with other creatives? — I’ve got two answers here: the philosophical one and the pragmatic one. I’ll start with the philosophical one because I always consider myself to be socially inclined without being too political because I’m apolitical [laughs]. There is a meritocracy in the collaborations, and that was an initial interest for me to get involved in collaborations, like an exchange of ideas and different archetypes, being able to speak further away from a culture that doesn’t have geography and borders. The pragmatic one is tooling and technology and IP—having access to tooling from larger conglomerates. It fords independence and new alchemy. There’s a real autonomy that comes with that. And those are the two reasons why I value collaborations and why it’s continued to grow.

I think collaborating is as important for a big brand as it is for a young designer; there’s a mutual benefit there. — Totally! As a young designer, you sometimes don’t realize what the actual relationship is. As time has gone on, it’s just strong to lean on the faculties of IP exchange for technology, tooling, and molds. It is really important, and it can be really honest.

Tell me about your recent collaboration with Hublot. — So that has been three years in the works. It is interesting. The name of the watch is Big Bang, but it is completely new movements and tooling; from the crown, the face, the strap—we made new molds for all of that. Its ticket price was $105 000, and we made 50 pieces—all sold out within a day. It was incredible to see the radical design, with a retail value of 7.1 million Euros, sold out in a day. And there’s so much more to come from this collaboration in terms of leveraging the technology that Hublot has and refining the storytelling. Really focusing on how the engineering and the material work Hublot has developed, like the titanium and Magic Gold, and the treatments they are developing can meet the sensibility of the now. And part of my role in that partnership is ensuring that the technology meets the user experience. It’s not just about the wearable product but the environment, the brand, and the brand behavior. I’ve redeveloped two of Hublot’s interior experiences within their Tokyo concept stores. And if you step into the store, you see the use of material and shape is quite radical compared to the typical boutique.

So, it’s like creating a total experience and not just the watch? — Yes, and right now, we’re talking about buildings with Hublot quite a lot.

Do you have a dream project? Whom would you like to work with next? — Hmm, interesting question. I don’t think I’d like to work with any of my idols. I don’t think it’s good to know them too well. Where’s the mythology, then? Yes, you’re probably right! — I think I’m already working with my dream collaborators right now. We have Nike, which will commence again in January. We will debut three new models. A lot is happening with Beats and Apple in the future. We have an EV vehicle I’m looking at right now, a motorbike. We also have projects in fragrance as well as in skincare.

“Objectively I think we’ve traded rapid growth for sensibility in fashion, and that’s a shame because there is a historic responsibility to procure, produce, and protect great articles of clothing that have meaning and tell stories. I think part of that reverence has collided too closely with late capitalism, and I think that compromise is too easy a decision for many people.”

— Dr. Samuel Ross

Could you tell us about the DSCENE cover you designed? What was the inspiration? — Yeah, I wanted something immediate. This flag we developed, it’s a flag of social values, and it typically represents immediacy and emergency. It was first created when we started our Black British Artist Grant program, and it kind of represents urgency for change. By the time this issue releases in print, we will have announced the next program recipients. We’ve also added the V&A to the advisory board alongside Grace Wales Bonner, who will be a guest editor. And the other image is a physical piece of artwork, the marble, and steel lounge chair that has this brutalist and modernist effect, and there’s, of course, me next to the chair. There’s a real balance of the social immediacy that are just as important as the physical works that we create. It’s almost an intangible world between what we do and the physical world, which is easier to understand. And the yellow—the urgency, the immediacy. Virgil always talked about the yellow that was on my website when he first went onto it to email me, and it always stood out to him. So the yellow is a bit of an ode to my friend and my mentor also.

Speaking about improving social equality, how do you think the industry can do better in those terms? — Well, I just wrote a quote for the design council over here. They were saying that only two percent of the total employment rate within the design industry in the UK is attributed to the black British and black Africans, and maybe four percent of South Asian and East Asian. So, there’s still a lot to be done with the initial educational system and how design is taught. I still have bad memories of being taught design at the school level and having difficulties feeling like I had a voice and space within the design community as a teenager. Much of it needs to be restructured in the educational system and how design and art are taught and valued. If you think of woodworking and carpentry, for example, you don’t think of them as artists’ work. So, there’s a lot of repositioning of the arts and crafts and craftsmanship that needs to happen. This will probably help equalize who can have a voice in design.

What do you think is missing in the fashion industry today? — Objectively I think we’ve traded rapid growth for sensibility in fashion, and that’s a shame because there is a historic responsibility to procure, produce, and protect great articles of clothing that have meaning and tell stories. I think part of that reverence has collided too closely with late capitalism, and I think that compromise is too easy a decision for many people. I would like to see a little bit more integrity across the industry from both designers, owners, and corporations in terms of why we are still making things reaffirmed.

What are our responsibilities towards our planet? Not just as people working in the fashion industry, but in general. — You know, I think our responsibility is kind of not to kill animals and eat them, nor to take their skin and wear it. I say this because I ended up joining a vegan protest in central London recently. But I’ve also been looking into plant medicine, and these things speak to you and bring clarity. We shouldn’t be killing our environment and its inhabitants if we are looking for some type of climatic piece.

I also have difficulty with the lack of consideration for the different types of intelligence that plants and animals inhibit to different properties and how we completely disregard those proximities. I think all of that kind of goes into sustainability. Because it’s about equality, awareness, consideration, and reducing trauma. It’s about considering one to be a part of the body and one to be a single object or article. I think there’s a lot that’s been lost.

Tell us about your first solo show this year. — There’s a real focus on the purist vision of fashion as an artistic tool for communication that will be considered with space, construction, material, and performance. It will help give people a little clarity of where I sit within fashion because I’m an artist in fashion. So, what would be shown is an artistic body of work, a noncommercial body of work—for the most part—and the broad body of work. There will also be incredible collaborations. I understand what my purpose is in the industry. It’s not to be a commercial workforce. It is to be the fourth leader into communicating how people are feeling and what they should be communicating now.

Originally published in DSCENE “Fever Dreams” Art Issue