Art duo ELMGREEN & DRAGSET has changed the way we relate to contemporary art, but also the way we consume it. Their permanent installations are turned into landmarks, such as the famed Prada Marfa, yet the duo has ventured into art with a performance piece titled “12 Hours of White Paint”.

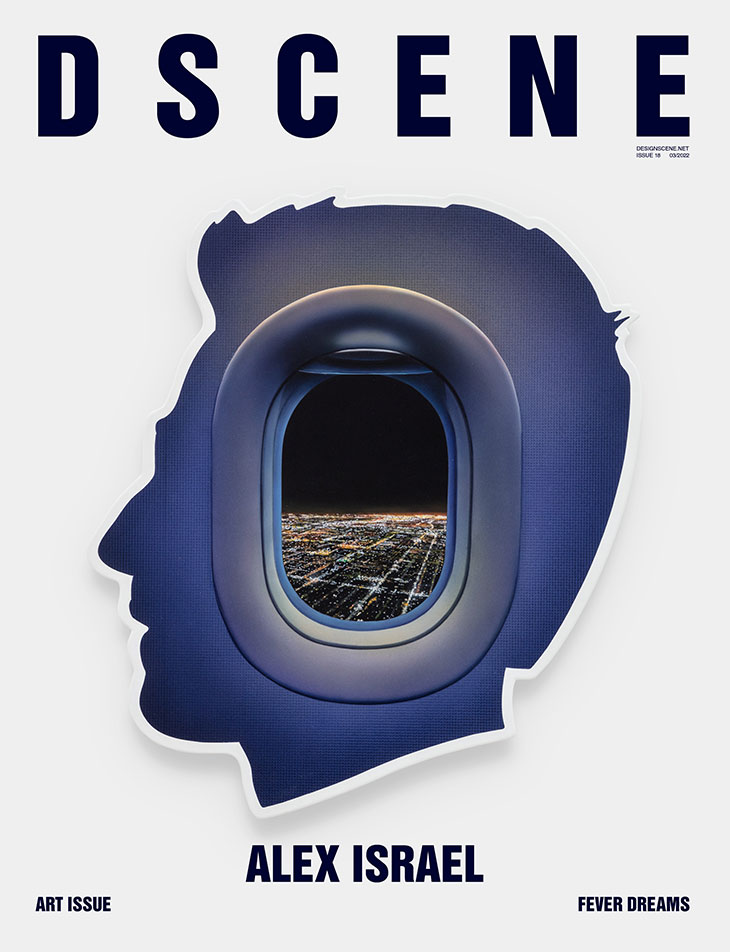

GET YOUR COPY OF DSCENE “FEVER DREAMS” ART ISSUE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

In our interview Editor KATARINA DORIC discusses with the duo the influence of one’s artwork, swimming pools, and non-corporeal existence.

In your work, we often see structures suspended from the ceiling, sunk into the ground, or turned upside down, creating the scenes one can see in a fever dream. Do they actually come from your dreams?

No, from daydreaming. We sometimes wish for a world that is slightly less rigid.

You often play with objects and their settings, but also their re-contextualization. How important is a fresh understanding of what you provide with your art for shaping societal and individual consciousness?

We don’t believe that individual artworks or even one artist’s oeuvre can change anything directly, but the sum of art and the ideas it carries can have a huge impact on people and societies over time. The impact of seeing things from a new angle or in a new context can help keep us on our toes, make us more alert, and open us up to other viewpoints.

Your works are very performative and call for the public to participate. Do you ever consider the audience’s reactions while creating new work?

We think a lot about the audience as a combination of a receiver, participant, and coauthor. In that sense, it is not exactly about achieving a specific reaction but rather a level of trust and willingness to play along.

“It can feel like our bodies are no longer the main agents of our existence in today’s world. They don’t generate value in our society’s advanced production methods like they did in the industrial era, and our physical selves seem to have become more of an obstacle than an advantage.”

— Elmgreen & Dragset

The scenes from your latest exhibition Useless Bodies? at Fondazione Prada are still etched on my memory. It was very powerful but, at the same time, disturbing. Is it important for art to be provocative?

Provocation alone can be pretty empty. There needs to be more added to a situation, other layers that can be obtained through various visual and social codes: ideas of beauty or ugliness, surface and depth, skill or improvisation; a sense of complicity or rejection, of learning and unlearning.

I found the scene of the empty pool particularly unsettling, and I can’t really explain why. You often use the pool motif in your art, so do you have the answer?

Swimming pools have complex social significance beyond their aesthetic qualities that we are drawn toward exploring. Private pools might be associated with the “American dream” or middle-class status and successes. In contrast, public pools can signal notions of community, such as public spaces where we can share physical experiences with one another and come together regardless of class or background. They are one of the few remaining public spaces where people can be undressed and at leisure in the company of others, which carries its own social significance. Our abandoned swimming pool works, however, tend to speak of issues of gentrification or the loss of public spaces and their importance in our lives. There’s an element of melancholy in that, the feeling of the end of play. Still, there’s also a slight melancholy in the very reason humans create pools: to imitate nature, to make a pond or lake substitute that fits into our every day, and often urban, landscapes.

“It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that we have real bodies that need all kinds of nourishment—mental, emotional, as well as physical. We have to think about the world as a whole. A purely non-corporeal existence cannot and will not happen.”

— Elmgreen & Dragset

The human bodies at the exhibition looked just too real. I couldn’t really look at them closely for more than a few seconds. Did you get a lot of similar feedback?

More people have commented on how many of our realistic human figures seem to be in their own world and how it is impossible to meet their gaze. They seem to almost withdraw from the viewer and the world around them. We find this interesting, as it creates a field of tension in the space.

You said the human body transformed from the 19th-century producer, through the 20th-century consumer, to the product that is today. Could you please elaborate on that? What do you think comes next? What is the future role of the body?

It can feel like our bodies are no longer the main agents of our existence in today’s world. They don’t generate value in our society’s advanced production methods like they did in the industrial era, and our physical selves seem to have become more of an obstacle than an advantage. Between shifts in our working cultures and our increasing dependence on technology, there seems to be less that our bodies can partake in. In addition, our data is gathered and sold by tech companies, making our bodies, movements, and habits products for corporations, and thereby commodities. We hope that space is made for our physical selves in years to come and that our bodies continue to hold importance in society. But perhaps the next step is to become one with machines.

In today’s world, our physical presence, in most cases, is not a necessity. We work remotely, meet via Zoom, and buy real estate in the metaverse. What do you think about the direction we’re heading in?

It’s important to keep reminding ourselves that we have real bodies that need all kinds of nourishment—mental, emotional, as well as physical. We have to think about the world as a whole. A purely non-corporeal existence cannot and will not happen.

What are your dreams for the future?

We dream of a wealth of encounters IRL that carry with them the promise of a digital world where race, religion, heritage, gender, and sexuality do not create hierarchies and animosity.

Originally published in DSCENE “Fever Dreams” Art Issue