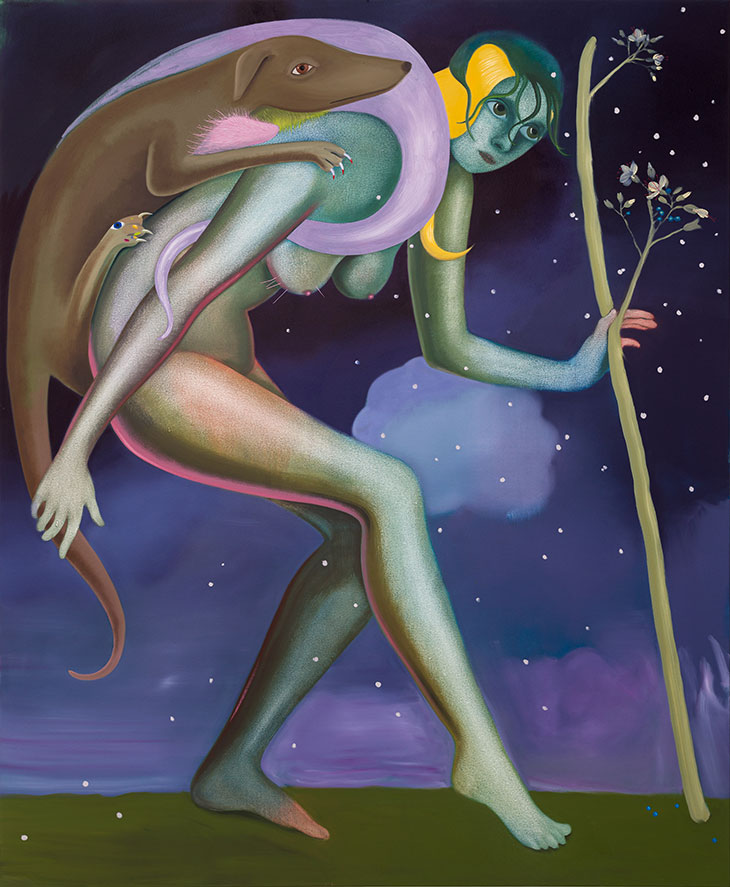

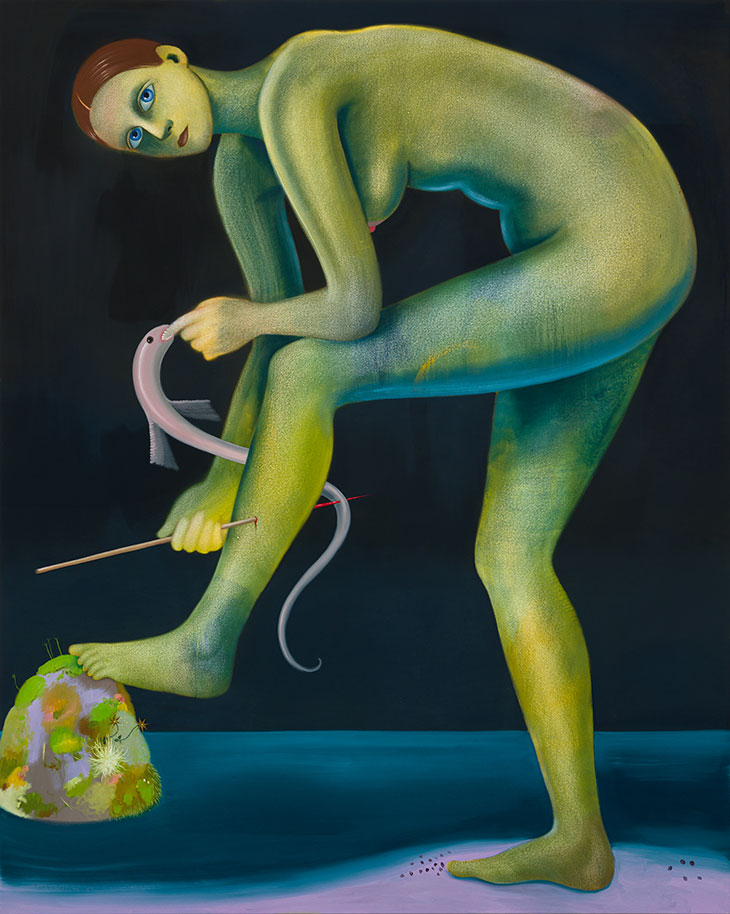

The female figures in Sara Anstis’s paintings have strange habits. In The Hunt (2022) a young woman with greenish hued skin appears to be spearfishing, except she has impaled her own left leg, which she attends to bent double, her breasts hanging down. In turn, the object of her prey, a long-tailed fish, seems to be surviving out of water, its mouth clamped over the woman’s left index fingers. In Knot (2022) a similarly svelte and naked woman ties a second to a tripod of firewood. We assume a pyre is about to be lit, but the victim’s eyes are closed and seem vaguely restful. A willing sacrifice perhaps. Certainly she expresses no more emotion than three women shown in Sleepers (2020), who, against a typically deserted landscape, snooze standing up against a series of curiously smooth wooden posts.

GET YOUR COPY OF DSCENE “FEVER DREAMS” ART ISSUE IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

Over dozens of canvases in the Swedish-Canadian artist’s most recent exhibition, at Paul Kasmin in New York, more slim nude women are depicted, largely blank faced and devoid of emotion, as they wrap themselves in dogs and snakes, cavort in water or read to a framed picture attached to a tree. Were these historical works, hung in a museum, one might turn to the information plaque by the side of the canvas for explanation as to what myth is being depicted in these surreal tableaux, what hidden meaning might be divined from Anstis’s scenes, but they are in fact purely of her imagination. Yet that does not mean to say they are devoid of narrative: Anstis is one of a number of female painters currently exploring notions of “monstrous” femininity, a questioning of what behaviour, in an increasingly censorious world, is expected from women.

In her 1993 study The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, the film theorist Barbara Creed challenged the predominant view of women in horror films as victims by writing on – and celebrating – examples in which females were shown as the monster. From Carrie and The Exorcist to the Alien trilogy, Creed noted that the monstrosity of female antiheroines is often related to their bodies and sexuality (from Carrie’s first period setting off her demonic possession to the tagline of Alien 3 – ‘The Bitch is Back’ – ambiguously referring either to the Alien or Sigourney Weaver’s strong female space cadet). The strange siren-like figures in Anstis’s painting are likewise chilling, and their nudity is shown not as a vulnerability but a strength. As is typical to her characters, in Lily (2022), a woman seems to be drowning another woman in a pond, but the artist draws the viewer’s eyes not to this murderous action but to the perpetrator’s swollen labia and red nipples. Such violence and nudity is apparent too in Emma Cousin’s work. Over a series of richly dramatic paintings shown last year at Niru Ratnam Gallery in London, figures, almost adrongenous, seem to devour and sink into each other. Charades (2021) shows five such figures – bald with saggy eyes and a marbled skin of red, yellow and orange hue – interact. One seems to be tonguing the eyes of another, who in turn vomits out the head of a third. Noses go into ears, fingers into noses. It’s a gross orgry. All the paintings in the show were titled after games, but Noughts and Crosses (2021) could equally refer to the orifices on display. Here too fingers enter the gaping circular mouths of three, perhaps four, intertangled women, while X-shaped vaginas are splayed. Such sexual explict content, in which bodies not just embrace each other, but skins and body parts seems to merge to the point of grotesquery, is a motif too of Canadian artist Ambera Wellmann. In Indirect Kiss (2020) amidst a forest of red poppies two female figures seem to either be tumbling from or reaching to the anus of a much larger figure. In Nosegaze (2020), two women embrace to the point that their legs become one spaghetti-like mass. In the vast, over two metre in length vista Orbit (2022) a crowd surrounds an orgy that is so frantic that distinct human forms all but disappear.

Enlargement is a technique employed by Gina Beavers, her close-up reproductions of images culled from make-up tutorials and stock images of ruby red lips and black long-lashed eyes, made even more terrifying by her rendition of them in bas-relief. Other works go further in their horror: Liz Phair ‘Parasite’ Butt Cake (2020) depicts the lower back to thighs of a woman lying on her front in sexy thong-like white knickers. Except an unseen hand is slicing a cake-like wedge from her left buttock. Inside, like a coloured sponge, a scene plays out between a man and woman. Hand Bra (2015) shows the torso of a richly tanned woman, her large breasts held in place with a bra seemingly made of human hands. The painting subverts an unwanted grope of male hands, by turning the violence back on the man (as if scream queen Marilyn Burns’s character in Texas Chainsaw Massacre had turned the tables on the film’s human face-wearing serial killer). Both the latter works are creepy nightmarish scenarios that, like the paintings of Anstis, Cousins and Wellman, can find precedent in earlier female surrealists.

Dorothea Tanning, who died in 2012 aged 101, brought female psychodrama to surrealism. Many of her works played out in domestic environments and, like the trope of entanglements present in the contemporary work of Anstis and Cousins, often involve female protagonists being tripped up or tied up by tenicular elements. It’s a motif that goes back to the Greek figure of Medusa, a female gorgon with living venomous snakes in place of hair, who had the power to turn men to stone. In one of her most famous works, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (1943), two girls are shown on a red-carpeted landing at the top of a grand staircase. A vast sunflower seems to have climbed the steps, its branches groping towards them. One girl’s hair stands on end and her dress unravels into strands. It’s an anxiety dream to claustrophobia. In Children’s Games (1942) another two girls rip down wallpaper to reveal sexualised body parts. A possibly adult body lies dead at their feet. The idea of sexual escape looms large. The perceived role of women as being trapped in the home – and dreams of freedom – also plays out in Leonora Carrington’s work in which women and wild animals often meet in the environs of staid drawing rooms and bedrooms. In her Self-Portrait (ca. 1937–38) the artist sits in an ornate playroom, her hand pointing towards a live hyena. A rocking horse, attached to the wall, looks out the window to a near-identical real horse galloping off through the wooded landscape beyond.

Given that the ‘monstrous feminie’ relies on dreamlike tropes, it is unsurprising, given the rich history of magical realism, to find it practised by a later generation of Latin American female artists too. Wilma Martins, the Brazilian artist who died in September this year aged 88, played with gender roles and tropes throughout her career. Return (1967), a woodcut print, shows dozens of tiny figures tumbling back into the volcanic form of a woman’s vagina. Above them a bevy of women look on inside an egg-like oval. Yet her greatest contribution to the genre is a series of paintings in which no human figure appears at all, but show animals and vegetation invading and rewilding scenes of bourgeois domesticity. Tiny antelopes reclaim the bedroom in one untitled 1974 drawing and watercolour. In another alligators roam a living room. Creed wrote “When women are represented as monstrous it is almost always in relation to her mothering and reproductive functions”: to abandon the domestic setting and allow untamed nature to take over might be the most horrifying – and liberating – act that a woman can embark on within the patriarchy. Likewise, while Wanda Pimentel’s paintings do not at first glance obviously feature ‘monsters’, there’s a chaotic disregard to the gendered roles of the patriarchy. One painting, created in lurid green and red, from the 1968 Involvement series shows just a pair of nude female legs trampling across a trashed kitchen worktop. There’s a sinister sense that the objects in disarray – knives, forks, a boiling kettle – could be weaponized. In further works in the late Brazilian artist’s series, other objects – belts, cigarettes, a saw, all shown alongside anonymous, languorous, sexy, legs – fulfil a similarly threatening role. Pimentel’s women are depicted as glorious rebels – femme fatales – with which, like all the subjects in all these examples of artistic feminist horror, we are invited to side with. Amidst the orgies, violence and witchery, there’s an enormous sense of liberatory fun. Collectively they lead us to question who are the sick ones in society, the entangled and sexually free, or the the society they monster.

Words by Oliver Basciano

Originally published in DSCENE Art Issue “Fever Dreams”