Alma Bektas is a multidisciplinary artist who transforms floral design into a medium of creative expression through botanical installations, scenography, and artistic direction. Her work spans exhibitions, costume design, and theater productions, reflecting a philosophy that highlights resilience over traditional notions of beauty. Alma gravitates toward prickly, untamed blooms with spiny leaves, appreciating their ability to thrive in challenging environments.

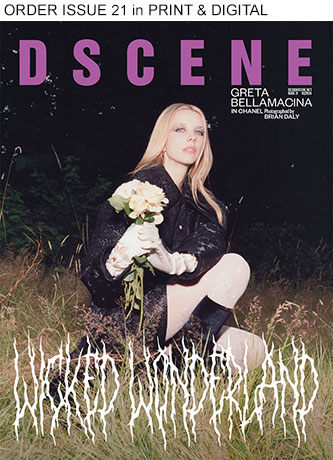

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT and DIGITAL

In this exclusive interview for DSCENE Magazine, editor Anastasija Pavic sits down with Alma Bektas to explore the layers behind her unconventional approach to floral design. Alma reflects on how impermanence shapes her creativity and hints at the ways her personal journey influences her work. She offers glimpses into her fascination with thorny plants and reveals how flowers carry meanings beyond aesthetics in her pieces.

Floral design can often be seen as temporary. How do you navigate the impermanence of your installations, and how does it impact your creative process?

Sometimes I imagine what it would be like if I were a painter, with all my paintings just sitting somewhere in the studio, waiting. The thought alone suffocates me. Working with flowers, which are so temporary, is perfect for me. I tend to get bored with things quickly, but this—this never gets old. With flowers, I feel secure, knowing that my creative mind won’t constantly jump from one hobby to another.

I also sometimes fantasize that my task is to create as many hybrid plants as possible and send them out into the world. Once they’re ready, they’ll unite and start attacking us humans to settle the debts we owe for everything we’ve done to the planet. Honestly, I wouldn’t mind if one of my creations ended up killing me. That death sounds somehow similar to the one when Steve Irwin was killed by a stingray while filming a documentary for Discovery Channel.

I’m not sure if this answers your question, though!

How has your upbringing or cultural background influenced your approach to art?

I grew up in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, and I was convinced that everyone there was an artist, even if they didn’t say it out loud. People developed the ability to make something out of nothing. You could see remarkable designs and innovations at every turn, with a special focus on repurposing and redesigning old objects. For the past 12 years, I’ve lived in Vienna, and it’s there that I truly learned the textbook definition of art. I’ve also noticed that many here call themselves artists, except they manage to make very little from a lot.

I never studied art, nor did I ever plan to become an artist. I think I just cheated the system. I dressed that unconscious Bosnian talent in Viennese makeup, and it seems to have created a good combination.

“Honestly, I wouldn’t mind if one of my creations ended up killing me. That death sounds somehow similar to the one when Steve Irwin was killed by a stingray while filming a documentary for Discovery Channel.”

Spiky plants often feature in your designs. What is it about these flowers that resonates with you?

True! At the heart of my creative journey is the thistle—it’s this perfect mix of resilience, defiance, protection, and beauty. Since I studied agriculture, I know it’s often seen as a problematic weed or a threat, but I see something different. It’s this amazing, complex plant, a beautiful blue flower with spiny leaves that protects it from being eaten by wildlife.

There’s that legend I love so much, the one where thistle once saved Scotland from a Viking attack. A Norse warrior, trying to sneak up on the Scots, stepped on a thistle in the dark, screamed in pain, and gave away their position. Thanks to that, the Scots were able to defend themselves. So, in a way, thistles have always been about protection and resilience, and I try to channel that same energy into my work.

Using flowers to create weapons introduces a dynamic tension in your pieces. What inspired this concept, and what message do you aim to convey?

Yes, my works often resemble weapons, but I see them as personal shields. When you live as a migrant in a foreign country, with no one to rely on, no money, and don’t speak the language, you become easy prey. You lose confidence, you feel very small, and struggle with the daily challenges of life.

With flowers, I finally found my lost language and unconsciously began building a protective barrier around myself through my work. I guess I wanted to say to everyone: now you can’t hurt me, and no, I won’t be your cleaning lady dankeschön (nothing against that job, which I’ve already done ofc, but you know what I mean).

Your floral installations carry a darker edge that goes beyond traditional notions of beauty. What informs this direction in your work?

I never saw it as dark. I think flowers have just been tied to poetry and “feminine softness” for way too long. There’s so much more to flowers than just beauty. I want to give them an animal energy that brings out their raw power—their relentless urge to grow and their natural way of breaking the rules. Some flowers have adapted to eat meat, and there are poisonous ones that can kill you. Flowers aren’t just delicate; they fight to survive and thrive, pushing through cracks in concrete, reclaiming space, and defying the limitations we place on them.

With your creations sometimes being worn, used as props, or standing alone as sculptures, how do you ensure they maintain their integrity while being adaptable?

I love making pieces that are interactive and wearable, and for me, the biggest and most interesting challenge is when I’m working on both the set design and costume design for a theatrical production. There the objects on stage can’t just stand still and look good—they need to be in constant motion. To ensure they maintain their integrity while being adaptable, I always focus on creating a solid, flexible base. For example, in one production, I collected fallen branches from the Wienerwald forest, wrapped them in black tape to maintain their stability, and added wheels so they could move across the stage. From their canopies, performers could remove head masks, which I made by covering old fighting masks with flowers. These elements moved, but their design and construction kept them sturdy and functional throughout the performance. For me in general, if the base is done right, that’s 70% of the work—If I get it perfect, the flowers will just surrender and say,”Do whatever you want with me.”

When selecting materials such as plastic and metal to complement organic components, what is your thought process in choosing the best fit for a particular installation?

Most of the artificial materials I use are recycled, sourced from the hoarder stash in my studio. I collect unrelated objects without a specific plan, and then an image of how they could come together often reveals itself naturally. I don’t usually plan in advance or engage in years of research before I start working. I guess, I tend to create first and then reflect on the meaning afterward. For example, I might find a discarded object—like a gun shape in the trash—and think, “Oh this would look great paired with flowers.” Later, I’ll realize that it was probably because I’ve been watching too many war documentaries again on Al Jazeera that day. My process is simply intuitive, led by what feels right in the moment, and I trust that the connection between the materials and the organic elements will emerge as the piece develops.

“I grew up in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, and I was convinced that everyone there was an artist, even if they didn’t say it out loud. People developed the ability to make something out of nothing. “

What impact do other forms of art have on your creative process, and how do you incorporate those influences into your work?

I’m that one horrible type who doesn’t really pay attention to the lyrics in a song—I just listen to the melody and imagine what it’s about. Or when I read or watch something, I barely remember the characters or the exact plot, but I just know to hold on to the emotion it left behind.

I often find myself returning to The Moomins, which I watched a lot while growing up. There’s something about that blend of beauty, melancholy, and quiet fear that has stuck with me over the years. The darker elements are always present, but they’re softened by this contrast with innocence and wonder. It creates an atmosphere that feels both comforting and unsettling at the same time. That emotional mix has stayed with me, and I think it naturally finds its way into my own work.

Actually, now that I think about it, that might explain why you thought my work has a dark edge to it—haha! It’s Moomin’s fault.

What’s your all-time favorite fairytale?

I know which one isn’t and that I have trauma from it: *The Little Match Girl*.

Is there a project or concept that you’ve been dreaming of creating for a long time?

You’re reading my mind because lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about a solo show, where I would turn the entire space into one world, from floor to ceiling. There would be everything, a whole floral battlefield. Anyone out there who wants to finance it?

Alma is redifining art ! Loving the feature and that she is finally getting some recognition

Alma needs a solo show ! This is damn gorgeous 🌸